The Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries transformed technology, the economy, and daily life. Today, we are living in the midst of a technological and internet revolution. While the terms for this modern transformation vary somewhat (information technology revolution, fourth industrial revolution, globalization, social media revolution), the impact on our daily lives is undeniable. The impact of our modern revolution may seem unique in the span of human history. However, many of these seemingly new trends are part of a much longer story of change. The following three examples can be useful in connecting the past to the present.

1. Language

New technology and its uses generate new words. Webinars, blogosphere, malware, and google are neologisms, newly coined words. Old words are often repurposed and redefined. A cloud is a white mass of vapor in the sky; it is also an online storage site for data. A footprint used to be just a mark left by a shoe; now it describes the traces you leave while browsing the internet. Trolls were characters in fairy tales; now they are people creating dissension online. Spam was processed meat in a can; now it is an unwelcome electronic communication.

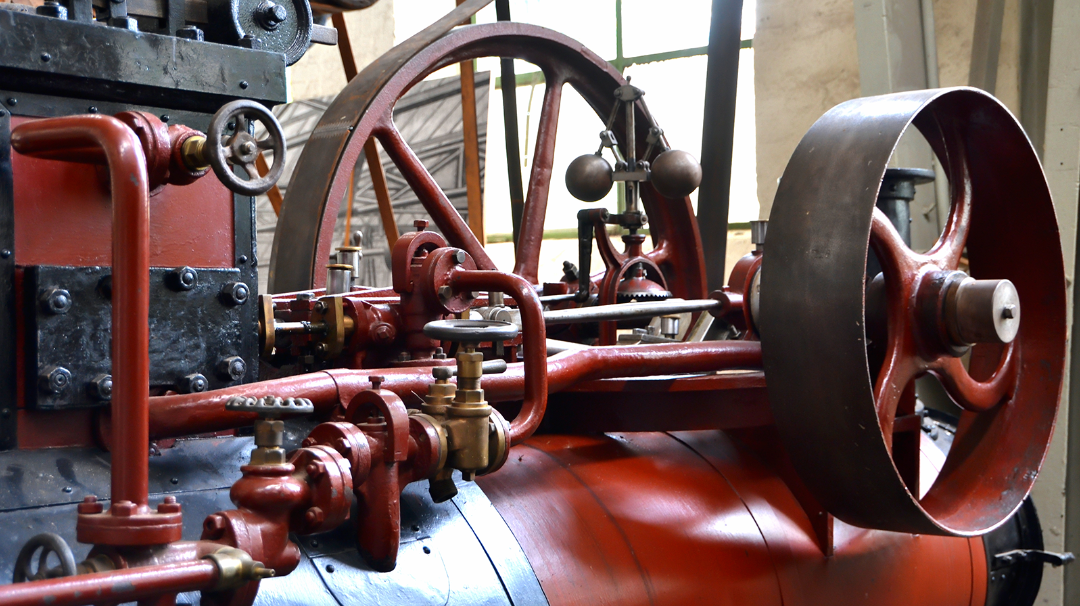

The word railroad was first used in 1757 to describe the carts on rails used to transport coal from mines. By 1813, railway was incorporated in the names of companies building and running train transportation networks. Industrial Revolution neologisms include lithograph (1828), camera (1840), airplane (1906), and typewriter (1868).

Older words were redefined. Before the eighteenth century, a factory was a group of traders in a foreign country or an inventory of goods. In the early 1700s, the word factory described buildings where goods were assembled. Before the 1830s, the word locomotive described travel; its meaning changed to refer to a self-propelled railway engine.

Encourage your students to examine this history of English words using the Oxford English Dictionary.

Source: Library of Congress

2. Vacations

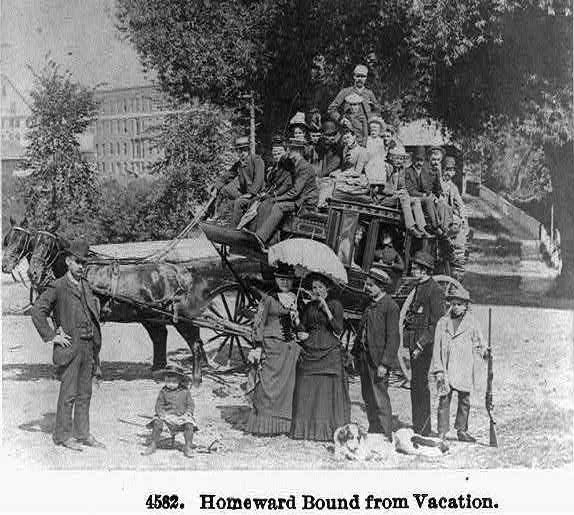

Only the wealthy could afford vacations before the mid-nineteenth century. Transportation by foot, horse, or boat was slow and expensive, and most people could not afford the costs of travel or the time away from work. The word vacation referred to the summer break of a student or teacher from school, not leisure travel.

By the late nineteenth century, the growth of railroads and canals and improvements in roads made travel faster and cheaper. The new industrial economy created a middle class of people with leisure time to take a few days or weeks to travel. The word vacation was adapted to describe recreational travel to restore physical and mental health.

Travel for leisure in the twenty-first century is affordable to even more people across the world. Mass tourism describes this growth of large numbers visiting popular destinations across the world. Instragrammability and Insta-worthy describe the positive and negative impact of social media on tourist planning decisions and tourist sites. On one hand, more tourist visits create more profits. On the other hand, too many tourists can have a negative impact on the environment. However, many people still can’t afford vacations, and American laws do not require employers to provide paid vacation time.

Source: Library of Congress

3. Funerals and Burial

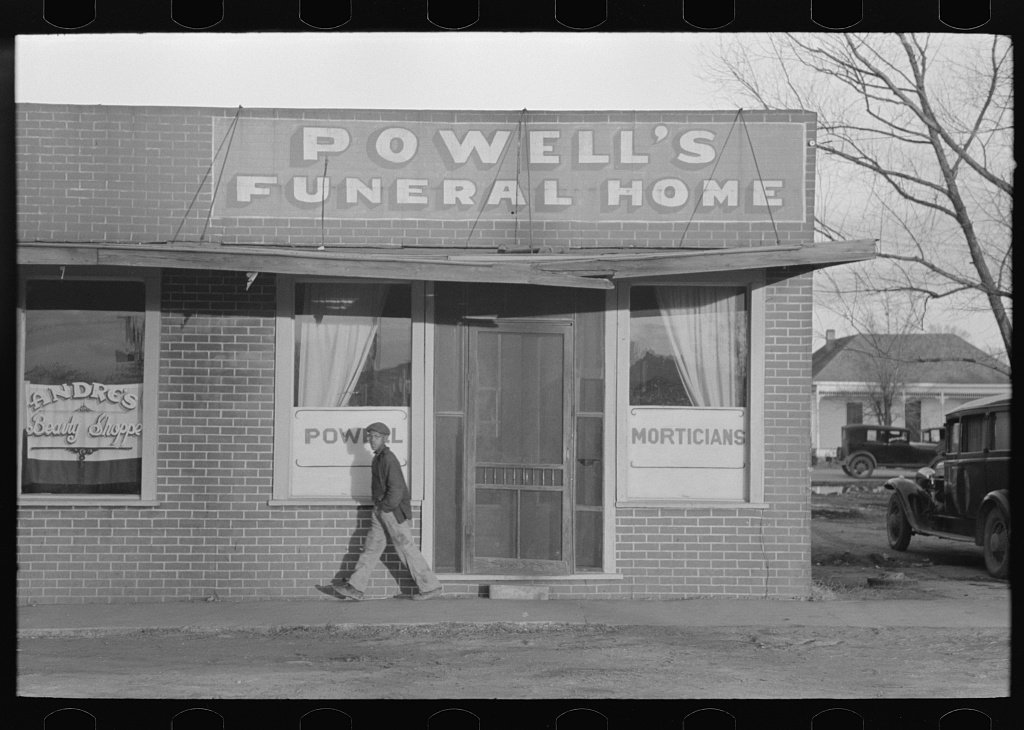

The Industrial Revolution changed how the deceased were prepared for burial. Before the late nineteenth century, funeral preparations were performed by family members at home. Before the Civil War, embalming was practically unknown; family members washed and dressed the deceased. For most average households, coffins and tombstones were ordered from local carpenters or stone carvers or made at home. Middle- and upper-class households might purchase items associated with death, such as mourning clothing, stationery, or monuments, but for most, burial was a simple religious and family affair.

Between 1850 and 1920, the modern, commercial funeral home industry developed. New services and products were introduced and marketed to mourning families. For a fee, professional undertakers chemically embalmed bodies for burial; provided coffins, mourning stationery, and other items required by mourning etiquette; arranged funeral and graveside services; placed newspaper obituary notices; provided hearses to transport the body to the cemetery; purchased the cemetery plot; and supervised the burial. Over time, funeral gatherings and services were moved from homes and churches to commercial funeral parlors or funeral homes.

Today, the internet revolution is changing funerals. Families can order tombstones and coffins online. Memorial websites are more common than newspaper obituaries, funerals can stream online for distant family members, and websites offer to capture the extracted DNA or the ashes of the deceased loved ones in lockets, keepsake jewelry, or works of art.

Comparing historical changes to similar shifts in the early twenty-first century can help students visualize the impact of new technology and illustrate both continuity and change over time.

Make history come alive in the classroom with simulation-based learning

Cynthia W. Resor is a social studies education professor and former middle and high school social studies teacher. Her dream job – time-travel tour guide. But until she discovers the secret of time travel, she writes about the past in her blog, Primary Source Bazaar. Her three books on teaching social history themes feature essential questions and primary sources: Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries: Modern Lessons from Historical Themes, Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies and Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies.