Socioeconomically disadvantaged students often come to school with lower level problem-solving skills than peers.

In our last post in this series on skills that help bridge the achievement gap, we discussed how bulking up on sequencing and processing skills can be a key part of closing the achievement gap between low-income and middle- to high-income students. In this post, our focus will be on problem-solving , another skill-set sometimes found lacking in students from poverty. With a little bit of professional learning around poverty awareness, you can help support students who might be in danger of falling behind.

What are problem-solving skills?

As discussed here, problem-solving skills refers to the ability to analyze and evaluate a problem, look for possible solutions, and select a potential solution based on some reasoned understanding and degree of consideration.

Click here to subscribe so you can get our upcoming posts about closing the achievement gap!

How do you know your students have trouble with problem-solving?

Sometimes it’s not obvious what poverty in the classroom looks like. According to Eric Jensen in Teaching with Poverty in Mind, some students have exaggerated responses because of survival mechanisms (Jensen, 2009). In other words, they have learned that the way to survive is to be the loud, squeaky wheel. They learn early to respond quickly and exaggeratedly to problems. This mechanism that serves them well at home follows them to school, and makes it difficult for them to think through solutions to problems.

1. Make sure students are taking think-time

One indication that students have trouble problem-solving is they don’t allow themselves think-time. This is because the inability to respond in appropriate terms hinders students’ ability to problem-solve because they’re not giving themselves enough time to problem-solve. Problem-solving requires think-time, meaning it takes a little time to make the best possible decision. However, for many of these students, the idea of taking the time needed to really think isn’t in their frame of reference.

To teach students about think-time, we as teachers must make visible how we process problems and find solutions, and give students opportunities in which they are provided sufficient time to develop problem-solving skills.

2. Give them a plan for problem-solving

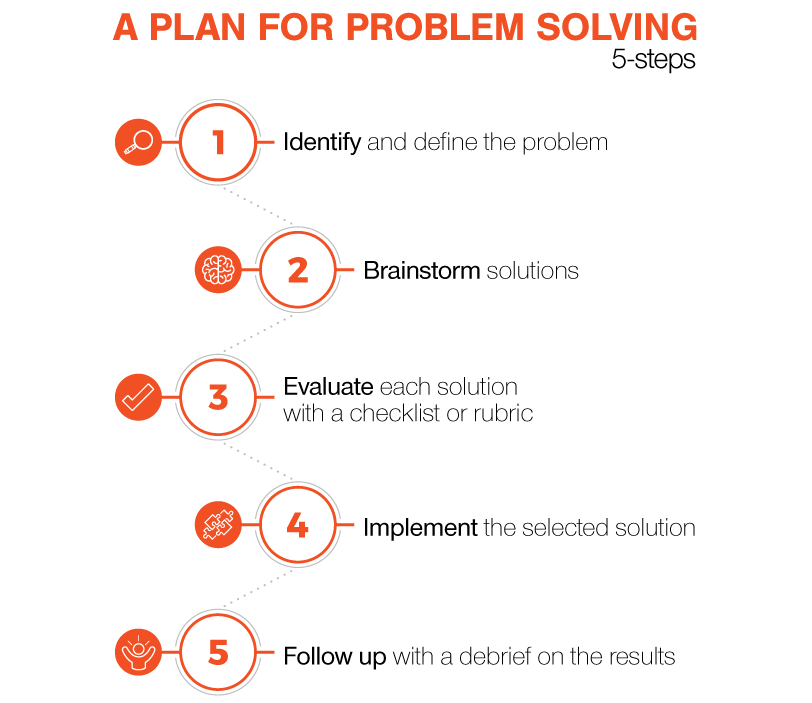

Jensen outlines a five-step plan for attacking a problem and finding potential solutions, which you can share with students:

- Identify and define the problem

- Brainstorm solutions

- Evaluate each solution with a checklist or rubric

- Implement the selected solution

- Follow up and debrief on the results

(Jensen, 2009)

Try sharing this list with students and have them work through it step by step while attacking a problem.

3. Give students opportunities to practice problem-solving

Jensen also suggests creating or simulating real-world problems to solve. This gives problem-solving exercises more of a connection to students’ lives or to social studies content, making it more meaningful and memorable for students. My mind immediately goes to important historical questions such as: Should Lincoln have let the southern states secede from the Union? Should the colonies have rebelled against England? Whatever topic you choose, there are so many ways to use these steps in your social studies classroom to help students build positive experiences with problem-solving in which they practice think-time.

If you’re looking for more skills to help low-income students catch up, check out my article on processing and sequencing skills, which are also important for closing the achievement gap. I hope that learning which practical skills students in poverty lack will help equip you to address this problem in your classrooms. Closing the achievement gap might be easier than we expected. Looking at the suggestion Jensen provides in Teaching with Poverty in Mind, the method isn’t “rocket-science,” it’s practical skills that any student can learn.

Consider: if every teacher made a conscious effort to teach problem-solving skills, how would school culture change? Do you allow your students think-time? Is closing the achievement gap a real possibility?

If you liked this, click here to learn about how sequencing and processing skills can help close the achievement gap for students

Would you like more professional learning resources?

Pam Gothart has been in education for 22 years including teaching high school social studies, and spent 12 years as a history director. Pam holds an Ed.S. from Samford University, where she focused her study on professional learning. She is passionate about education and helping teachers to be unique and effective leaders.