March marks Women’s History Month, which is a whole month to celebrate the specific achievements made by women throughout history, but these accomplishments can be highlighted throughout curricula all school year long!

While there are many historical contributions of women that teachers can highlight, consider taking a multi-disciplinary approach and celebrate women in science. Use this list in the social studies or science classroom to inspire and engage your students by having them select one notable woman from the list below (or students can find their own through research) and reflect on the individual’s achievements, not to exceed one paragraph. Then, have them share their reflections with the class in a discussion-based activity. Include essential questions to guide their learning and inquiry, for example, how are their scienctific contributions still impactful today or why did the student choose that individual?

We highlight five women below who are remembered for their contributions in science, but encourage you and your students to visit the National Women’s History Museum to research additional contributions of other women from other fields as well.

Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Franklin was a British biophysicist whose work played a crucial role in understanding the structure of DNA, RNA, viruses, coal, and graphite. Born on July 25, 1920, in London, England, Franklin showed an early interest in science and attended Newnham College, Cambridge, where she studied chemistry. She later earned a Ph.D. in physical chemistry from the University of Cambridge. Franklin’s most notable contribution to science came during her time at King’s College London, where she worked on X-ray diffraction techniques to study the structure of DNA. In 1952, she produced the famous Photo 51, an X-ray diffraction image of DNA that provided critical evidence for the helical structure of DNA. This image revealed the telltale “X” pattern characteristic of a helix and provided key insights into the molecule’s dimensions.

Unfortunately, Franklin’s work on DNA was undervalued and overshadowed during her lifetime. Without her knowledge, her colleague Maurice Wilkins showed Photo 51 to James Watson and Francis Crick, who were also working on elucidating the structure of DNA. Watson and Crick used Franklin’s data, along with other researchers’ work, to formulate their model of the DNA double helix, which they published in 1953. Although they acknowledged the influence of Franklin’s data, they did not credit her in their initial paper. Franklin’s contributions to science extended beyond DNA. She made significant advancements in understanding the structures of viruses, including the tobacco mosaic virus and the polio virus. Her work on the structure of coal and graphite also provided valuable insights into the properties of carbon materials.

Tragically, Rosalind Franklin’s life was cut short when she died of ovarian cancer on April 16, 1958, at the age of 37. Despite her untimely death, her legacy in science has been increasingly recognized and celebrated in the years since. Her contributions to the discovery of the DNA structure have been acknowledged, and she is remembered as a pioneering scientist whose work paved the way for future research in molecular biology and genetics.

Marie Curie

A pioneering physicist and chemist, Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and remains the only person to have won Nobel Prizes in two different scientific fields (Physics and Chemistry). Her groundbreaking research on radioactivity paved the way for advancements in medical science and radiation therapy. Curie’s early life was marked by hardship and perseverance. Despite facing financial struggles and discrimination against women in academia, she pursued her passion for learning and obtained a degree in physics from the University of Paris in 1893, where she met her future husband, Pierre Curie.

Mae Jemison

Mae Jemison is an American engineer, physician, and former NASA astronaut who made history as the first African American woman to travel into space. Born on October 17, 1956, in Decatur, Alabama, Jemison was raised in Chicago, Illinois. From a young age, she displayed an avid interest in science and space exploration, inspired by the Apollo missions of the 1960s. After completing high school, Jemison attended Stanford University, where she earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Chemical Engineering. She later pursued her passion for science and medicine at Cornell University, obtaining a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) degree in 1981. Jemison’s diverse academic background reflected her multidisciplinary interests and set the stage for her future career as an astronaut.

Jemison’s journey to becoming an astronaut was marked by perseverance and determination. She applied to NASA’s astronaut program multiple times before being selected as one of fifteen candidates from a pool of over 2,000 applicants in 1987. In 1992, she made history by becoming the first African American woman to travel in space when she flew aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour on mission STS-47. During her eight-day mission, Jemison conducted scientific experiments in materials science, life sciences, and human adaptation to space. Her accomplishments in space marked a significant milestone for diversity and inclusion in the field of space exploration, inspiring countless individuals, particularly women and minorities, to pursue careers in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics).

Following her historic spaceflight, Jemison left NASA to pursue other ventures. She founded the Jemison Group, a technology consulting firm, and became involved in various initiatives aimed at promoting science education and advancing opportunities for underrepresented groups in STEM fields. Jemison is also a passionate advocate for environmental sustainability and the intersection of science, arts, and culture. Throughout her career, Mae Jemison has received numerous honors and awards for her contributions to science and education, including the National Women’s Hall of Fame and the International Space Hall of Fame. She continues to be an influential figure in promoting STEM education and inspiring the next generation of scientists, engineers, and explorers to reach for the stars.

Ada Lovelace

Ada Lovelace, born on December 10, 1815, in London, England, is often regarded as the world’s first computer programmer. She was the daughter of the famous poet Lord Byron and Anne Isabella Milbanke, Baroness Wentworth. Lovelace’s upbringing was marked by a blend of intellectual stimulation and rigorous education, reflecting her mother’s commitment to providing her with a well-rounded education in mathematics and the sciences. Her interest in mathematics and logic was apparent from a young age. She was tutored by prominent mathematicians and scientists of the time, including Mary Somerville and Augustus De Morgan, who recognized her exceptional talent and intellect. Lovelace’s education in mathematics and her exposure to the scientific community of London provided her with a solid foundation for her future contributions to computing.

Lovelace’s most significant collaboration was with Charles Babbage, a mathematician, and inventor known for his designs of early mechanical computers, such as the Difference Engine and the Analytical Engine. In the 1840s, Lovelace became acquainted with Babbage and his work, and she became particularly intrigued by the Analytical Engine, a theoretical mechanical general-purpose computer designed by Babbage. Her most notable work is her translation and extensive annotations of an article about the Analytical Engine written by the Italian mathematician Luigi Federico Menabrea. In her notes, which are often referred to as the “Notes by the Translator” or simply “Ada’s Notes,” Lovelace presented a detailed explanation of how the Analytical Engine could be programmed to perform various tasks beyond mere number crunching. She outlined a method for calculating Bernoulli numbers using the Analytical Engine, making her the world’s first computer programmer. Lovelace’s insights were groundbreaking because they went beyond the capabilities of the technology of her time. She envisioned the potential of computing machines to perform tasks beyond simple arithmetic, including music composition and scientific analysis. Lovelace’s visionary ideas laid the groundwork for modern computing and algorithms, anticipating concepts such as computer programming languages and software.

Despite her significant contributions to the field of computing, Lovelace’s work was not widely recognized during her lifetime. It was only in the mid-20th century that her notes were rediscovered and her contributions to computer science were fully appreciated. Today, Ada Lovelace is celebrated as a pioneer of computer science and a symbol of women’s achievements in STEM fields. Her legacy continues to inspire generations of scientists, engineers, and mathematicians to push the boundaries of innovation and pursue their passions in technology and computing.

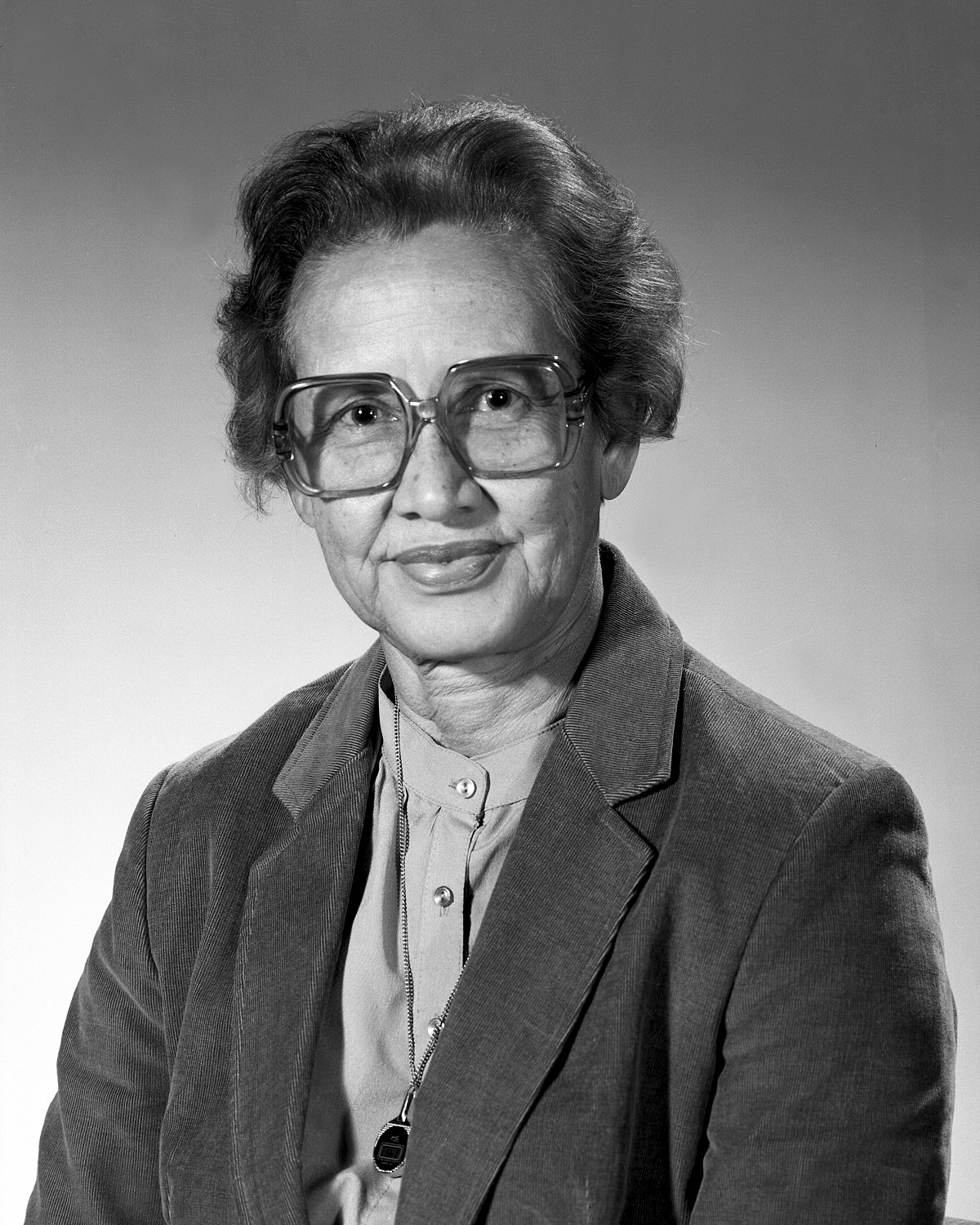

Katherine Johnson

Katherine Johnson was a pioneering African American mathematician whose groundbreaking contributions to space exploration played a crucial role in NASA’s missions during the early days of the space program. Born on August 26, 1918, in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, Johnson demonstrated exceptional mathematical abilities from a young age.

Despite facing racial and gender discrimination, Johnson pursued higher education, earning degrees in mathematics and French from West Virginia State College. In 1953, she joined the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which later became NASA, as part of the agency’s “Computer Pool,” a group of African American women mathematicians tasked with performing complex calculations by hand. During her tenure at NASA, Johnson’s mathematical prowess became legendary. She played a key role in calculating trajectories, launch windows, and orbital mechanics for some of the agency’s most historic missions, including Alan Shepard’s first American manned spaceflight in 1961 and John Glenn’s orbital flight around the Earth in 1962.

One of Johnson’s most significant contributions came during the Apollo 11 mission, which successfully landed the first humans on the Moon in 1969. She played a critical role in calculating the trajectories that guided the spacecraft to the Moon and back to Earth, ensuring the safety and success of the mission. Despite working in a field dominated by white men, Johnson’s talent and dedication earned her the respect of her colleagues and paved the way for other women and minorities in STEM fields. Her contributions to space exploration were recognized in 2015 when she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the United States.

Katherine Johnson’s remarkable career and legacy have inspired countless individuals and highlighted the importance of diversity and inclusion in science and engineering. Her story was immortalized in the book and film “Hidden Figures,” bringing her achievements to a wider audience and cementing her place as a trailblazer in the history of space exploration. Johnson passed away on February 24, 2020, at the age of 101, leaving behind a legacy of excellence and perseverance that continues to inspire future generations.

Seeking more lessons to celebrate women and integrate multidisciplinary lessons all year round?

Sign up for a free 30-day trial of Active Classroom

Monet Hendricks is the blog editor and social media/meme connoisseur for Social Studies School Service. Passionate about the field of education, she earned her BA from the University of Southern California before deciding to go back to get her master’s degree in educational psychology. She currently attends the graduate program at Azusa Pacific University pursuing advanced degrees in school psychology and Applied Behavior Analysis. Her favorite activities include watching documentaries on mental health and cooking adventurous vegetarian recipes.