Quacks love health crises, and the COVID-19 virus has become very lucrative for people who make claims about unscientific cures. In recent months, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued warnings to several companies who are promoting fraudulent products. These companies deceptively claim their products can treat or cure the virus. Modern teas, oils, and other treatments are not scientifically proven to be effective, yet customers are desperate enough to fall for these “curative” products. This isn’t to say holistic and alternative medicines do not have healing properties for some, but overall the efficacy of these products and practices is largely unproven by evidence-based research.

This has become a common theme throughout our history. Quacks promote fake cures and humans fall for the quick-fix advertisements. The question is, why?

Using current and historical advertisements and media promoting questionable cures, give your students the opportunity to explore and analyze economic and cultural tactics that quacks have employed in the past and continue to use today.

Quacks manipulate our fear

Quacks manipulate our worst fears, especially fear of illness, disability, our own death, and the death of loved ones. Fear easily overwhelms our ability to think rationally and critically. One hundred years ago over twenty-five million Americans were diagnosed with the flu in the 1918-19 influenza pandemic. At least 670,000 Americans died. Quack cures offered frightened Americans false hope. At the time, numerous quack cures were promoted in print advertising to take advantage of the fears. You can find some great examples from the early twentieth century here.

Quacks seek out the most vulnerable

Medical treatments and health insurance are expensive, but quacks seek out people struggling to pay the bills, and offer cheaper alternatives. Advertisements often contrast the low cost of a purported cure with the high cost of scientifically proven medical treatments.

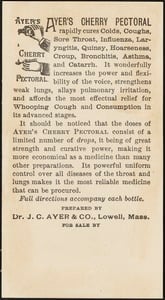

In the late nineteenth century, Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral was advertised as a cure for influenza, asthma, whooping cough, and consumption (tuberculosis). In reality, it cured none of those diseases. Advertisers wrote their ads to appeal to those seeking inexpensive medical treatment with the following information: “It should be noticed that the doses of Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral consist of a limited number of drops, it being of great strength and curative power, making it more economical as a medicine than other preparations.”

Quacks claim the “establishment” is the enemy

Conspiracy theories are a favorite of quacks. Those selling fake cures often tap into existing doubts about influential or powerful groups. In the 1920s, Harry Hoxsey, a salesman with no medical training, claimed his mixture of herbs could cure cancer. Thousands listened to his radio broadcasts and sought his “cure.” Hoxsey focused his sales pitches to rural Americans, claiming scientific research, medical experts, the government, cities, and the elite were the real problems.

“Everybody is using it!”

Modern quacks seek to create a “buzz” about their products, hoping word-of-mouth, emails, and viral social media posts will convince new customers to buy their cures. Sometimes information about a popular but fraudulent cure is reported on mainstream media, lending an air of legitimacy to the product. The message is created that “everybody is using it.” However, popularity and publicity do not equate to effectiveness.

To create buzz in the late nineteenth century, Dr. Kilmer’s Indian Cough Cure Consumption Oil claimed it was “The People’s Favorite.” Advertisements in the form of trade cards were distributed promising a money back guarantee and a free “Guide To Health” booklet with testimonials from people who had been “cured.”

Source: Digital Commonwealth – Boston Public Library

Analysis in the Classroom

Humans are quick to latch onto anything that can soothe their fears and anxiety about health. This is especially true in the pandemic playing out in real time. History is currently repeating itself, which provides a great opportunity for students to compare and contrast past human and government responses during earlier pandemics to those today. Using primary sources, students can analyze past advertisements, similar to the examples above, and interpret for bias. Research can also be done on proven evidence-based cures with scientific results versus quack cures.

NOTE: To adapt any of these historical themes to remote learning, we recommend utilizing this blog content in conjunction with online curriculum resources and lessons from Active Classroom or the Library of Congress. This blog can be sent to students to provide context for remote history assignments or long-term projects analyzing the pandemic.

Seeking more historical sources for your classroom?

Access a free 30-day trial of Active Classroom.

Cynthia W. Resor is a social studies education professor and former middle and high school social studies teacher. Her dream job? Time-travel tour guide. But until she discovers the secret of time travel, she writes about the past in her blog, Primary Source Bazaar. Her three books on teaching social history themes feature essential questions and primary sources: Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries: Modern Lessons from Historical Themes; Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies and Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies.