“If it looks like a conspiracy, it’s a conspiracy. If it doesn’t look like a conspiracy, it’s definitely a conspiracy.” Rob Brotherton, Suspicious Minds.

We have probably all encountered numerous examples of conspiracy thinking in recent years, including claims that COVID-19 vaccines contain 5-G chips, Democratic Party leaders are shapeshifting reptiles, and the exhaust from airplanes are full of chemicals to wipe out the American food supply.

The case of Edgar Welch is especially noteworthy. He believed a conspiracy theory that there was a sex trafficking ring in the basement of Comet Pizza. In December 2016, he stormed into the pizza place and fired his rifle in his search of the alleged sex traffickers. He received a four-year prison sentence.

Of course, real conspiracies do exist. For example, John Wilkes Booth was part of a conspiracy to assassinate President Lincoln. Tobacco companies already knew that cigarettes caused cancer, but kept the evidence quiet. Sometimes, then, it may be useful to speculate the possible existence of secret plans to do others harm. Yet, we also want our student citizens to learn skills to reject obviously false conspiracy theories.

Teach the Analysis Skills to Combat Conspiracies

So, how do we educate students to separate theories that might potentially unearth a real conspiracy from conspiracy theories that are clearly or most likely false? History class is an ideal place for teaching the critical thinking skills helpful for separating real from false conspiracy theories, for two reasons:

- Students are not emotionally involved in most topics in history. For example, it is unlikely that students would have a strong opinion on the causes of the War of 1812. Thus, students can be more objective in evaluating conspiracy claims in history.

- Based on outcomes and evidence, we may be able to see with some clarity which conspiracy theories in the past proved to be true and which were shown to be false. In this case 20-20 hindsight could be valuable!

The experience of encountering conspiracy thinking in the past can provide historical context for conspiracies today. As students see that most (but not all!) conspiracy theories in U.S. History were false or probably false, they should become more skeptical and discerning of conspiracy theories. A healthy skepticism of conspiracy theories is vital to citizenship.

In this lesson excerpt on the Civil War era, students are confronted with two conspiracy theories. (There are five conspiracies in the full lesson. You can view the full lesson here.)

For each conspiracy theory students put a #1 on the line to show how confident they are that the claim is true. They then review guidelines for evaluating conspiracy theories and revise their confidence level for each theory. In Part 3, they read evidence on each conspiracy theory and revise their confidence level again.

Sample Lesson

Civil War, Reconstruction, 1860-1875

Part 1: Evaluate Conspiracy Claims

Each of these claims is a conspiracy theory, by which we mean “(1) a group, (2) acting in secret, (3) to take power or hide truth, (4) to the detriment of the common good.” What is your evaluation of each of these conspiracy theories? Mark each item with your confidence that it is true.

- 100% It is definitely true. I’m confident it is true.

- 75% It is probably true

- 50% It may or may not be true

- 25% It is probably not true

- 0% It is definitely not true. I have no confidence in this claim.

1860: American presidents elected in years ending in zero, at 20-year intervals, starting in 1840, have died in office (1840, 1860, 1880, 1900, 1920, 1940, and 1960). This curse of Tecumseh (an Indian leader in the early 1800s) was started by Tecumseh’s brother as revenge against white settlers and soldiers.

Put a #1 on the line to show how confident are you that this claim is true.

100% 75% 50% 25% 0%

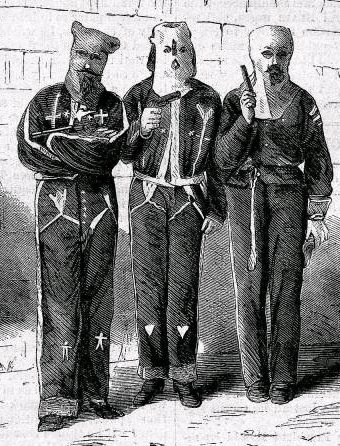

1860s and 1870s: The Ku Klux Klan and other white terrorist organizations conspired to use violence to deprive freedmen of their rights, especially the right to vote.

Put a #1 on the line to show how confident are you that this claim is true.

100% 75% 50% 25% 0%

Part 2: Conspiracy Detection Kit

These are some guidelines from a conspiracy detection kit by a researcher who studies conspiracies:

- Without convincing evidence, a conspiracy theory is less likely to be true.

- A conspiracy theory that involves super powerful people (for example, people who dominate the whole world or large parts of the world) is less likely to be true.

- The more elements involved and the more people involved, the less likely a conspiracy theory is to be true.

- The larger the conspiracy (world domination), the less likely a conspiracy theory is to be true.

- If the author of a conspiracy theory is suspicious of people or government in general, then it is less likely to be true.

- If a conspiracy theory cannot be falsified, then it is less likely to be true.

- If a conspiracy theory doesn’t line up with the way the world normally works, then it is less likely to be true.

After reading through the conspiracy detection kit, go back to the two conspiracy claims and put a #2 on the lines to show how confident you are that each claim is true. If you didn’t change your mind, just put the 2 above the 1. If you did change, explain the main reason why you changed your confidence in that claim.

Part 3: Evidence

Here is evidence that has been found for both of the conspiracy claims:

Item A, Presidents dying in office

Evidence:

- There is no evidence that any Indian stated the curse.

- There is no evidence that the curse caused these deaths.

- The conspiracy theory was popularized in 1931, by Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, a company that had publications and museums focused on strange events.

- Presidents elected in 1980, 2000, and 2020 did not die in office.

Item B, KKK violence

Evidence:

- Freedman Abram Colby testified to a Congressional Investigating Committee in 1871 that about 65 disguised night riders came to his house, took him outside to the woods, whipped him for three hours, and left him for dead.

- General J.J. Reynolds, military commander in Texas, reported on lawlessness in Texas in September, 1868: “The precise objects of the organizations [Ku Klux Klan] cannot be readily explained, but seems, in this state, to be to disarm, rob, and in many cases murder Union men and negroes…. The murder of negroes is so common [in Texas] as to render it impossible to keep an accurate account of them.”

- The majority report of a Congressional Investigating Committee concluded that the Klan did exist, that many of its members had evaded punishment for their crimes, and that the “terror inspired by their acts, as well as the public sentiment in their favor in many localities, paralyzes the arm of civil power.”

- A Georgia paper stated in November 1871 that the Klan “has existence only in the imaginations of President Grant and the vile politicians who have poisoned his ears with false and malicious reports… The reports of collisions between armed bands of Ku-klux and federal troops are utterly false, base, and slanderous fabrication….”

- According to a historian, in the 1868 Election, 2000 freedmen were murdered in Arkansas and 1000 in Louisiana by members of the Klan to prevent Republicans (which supported rights for freedmen) from voting. Democrats easily won those states.

- About 1000 members of the Klan were convicted of interfering with voting by black freedmen.

After reading the evidence, go back to the two conspiracy claims and put a #3 on the lines to show how confident are you that each claim is true. If you didn’t change your mind, just put the 3 above the 1 or 2. If you did change, explain the main reason why you changed your confidence in that claim.

Conclusion

The step-by-step procedure in the lesson is similar to Bayesian philosophy that argues that people should revise their hypotheses in light of new evidence. We want students to think carefully about conspiracy theories and consider evidence in their assessments. Conspiracies in history provide both objectivity for careful analysis and evidence for assessment. If we can train students to think about toolkit guidelines and to look for evidence in response to conspiracy theories, that will be a worthwhile accomplishment, indeed!

Learn about the ways Social Studies School Service can help build capacity in your district: Partner with us

DISCOVER NOW

Sources

Brotherton, Rob. Suspicious Minds. New York: Bloomsbury, 2015.

Bryant, Jonathan. “Ku Klux Klan in the Reconstruction Era.” October 2002. New Georgia Encyclopedia. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/ku-klux-klan-in-the-reconstruction-era/

Cortada, James and William Aspray. Fake News Nation. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

Fee, Christopher and Jeffrey Webb. Conspiracies and Conspiracy Theories in American History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2019.

PBS. “Grant, Reconstruction and the KKK.” American Experience, WGBH. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/grant-kkk/

Shermer, Michael. Conspiracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022.

Webb, Jeffrey. Conspiracy Theories. New York: Bloomsbury, 2024.

Kevin O’Reilly taught history for 39 years, all but four of those years at Hamilton-Wenham Regional High School in Massachusetts, where he also coached basketball. He is the former NCSS Social Studies Teacher of the Year, along with several other awards, and is the author of 31 books on critical thinking and decision making in history. You can see his biography and free critical thinking lessons at http://www.criticalthinkinginhistory.com.