Cemeteries are trendy destinations. Cemetery tours feature the rich, the famous, the macabre, and ghosts. However, cemeteries can teach students about primary source artifacts and several other important social studies themes.

Changing cemetery styles reflect the era

Burying grounds and cemeteries have a history reaching far back to the beginning of time. Their appearances and locations are unique to each culture. In America, Native American practices associated with death varied by location and cultural group. The early colonists followed European customs, preferring burying grounds near a church. However, churches were often distant from pioneer homesteads. Therefore, American family burial grounds became common, a custom that broke with European examples.

By the late 1700s and early 1800s, many of the graveyards in large, east coast cities like New York or Boston were becoming overcrowded. People became concerned about the effect of cemeteries on the health of the living. Even though scientific theories on the spread of disease were not fully understood, many believed that graveyards could exude gasses that caused disease.

New burial grounds were required, and Americans were influenced by a new style of cemetery popular in England and France. The first “garden” or “rural” cemetery in Europe was France’s Pere Lachaise, located on the outskirts of Paris in 1804. The term “rural” did not refer to remote, country cemeteries, but ones located on the outskirts of major cities, close enough that urban residents could travel easily by carriage or train to visit.

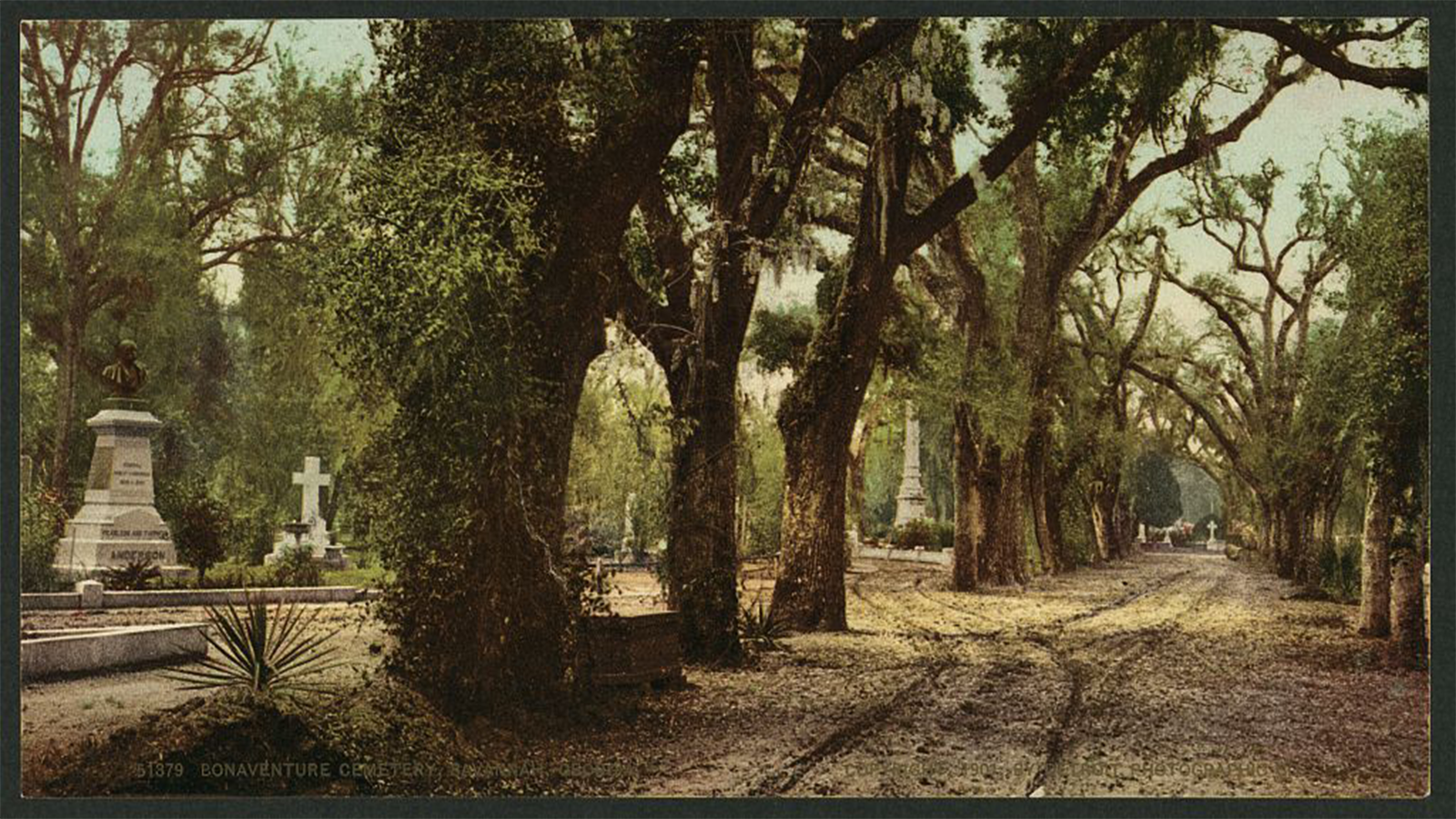

The first American rural cemetery was Mount Auburn, constructed on the outskirts of Boston in 1831. Many other cities followed the trend. Rural cemeteries differed from previous churchyard or family cemeteries because they were not associated with a particular faith or one family. Instead, they were created as corporations, and the lot-holders became shareholders. Anyone with the money to buy a lot could be buried there. These new cemeteries were not just a place to bury the dead; they became beautiful, landscaped parks that many visited to admire the scenery and impressive monuments.

By the early 20th century, the rural cemetery style began to decline. Beliefs about death and the afterlife were changing. The invention of power mowers discouraged the complicated landscaping of the rural cemetery. Pushing or riding a power mower between straight rows of evenly spaced monuments was quicker and more required fewer groundskeepers. Also, the funeral industry became commercialized. The dead were no longer cared for by the family, but by a professional funeral director that arranged every aspect of the funeral and burial. Mass-produced monuments also became much more standardized.

Credit: Library of Congress

Tombstone symbols: Old images with new meaning

Cemetery and tombstone symbols have been reused and reinterpreted for thousands of years. Religious symbols are especially popular in cemeteries. Over the millennia, an enormous variety of animals, plants, human figures, and other objects symbolized every aspect of religious practice. However, one can’t assume that symbols have the same meaning in different cultures, religions, and historical eras.

For example, the ancient Egyptians used pyramids, obelisks, sphinxes, and various symbols for monuments, temples, and tombs. Everything Egyptian became stylish again in 19th-century cemeteries, even though the meaning of these symbols had lost their original association with the polytheistic religion of ancient Egypt. (For more information, visit Egyptomania: Reviving Ancient Symbols in 19th Century Cemeteries.)

The economics of cemeteries

Archeologists and anthropologists study the remains of burial grounds and tombs to piece together the history of past cultures. Grave goods (items buried with the deceased) reveal patterns of long-distance trade and local production of goods. For example, coins with Islamic inscriptions have been discovered in Viking graves in Norway and Sweden, demonstrating the vast trade networks of the 9th and 10th centuries.

In the earliest American family or church cemeteries, monuments were often carved from local stone. For example, brownstone, a dark sandstone, is common in early New England cemeteries. However, as transportation networks improved, stone or finished tombstones were ordered from distant locations. Vermont granite was especially popular after the Civil War, delivered to distant locations via the railroad. Today, around one-third of American tombstones originate in the Barre, Vermont granite district.

Throughout history, funerals, cemetery plots, and elaborate monuments have been expensive; therefore, cemeteries become records of the socioeconomic hierarchies of a community. In general, the graves of the poorest people are invisible or unremarkable because of the cost associated with burial. The graves of the wealthiest were often featured in the front and center of the cemetery, especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the 21st century, a cemetery burial and monument typically cost more than $9,000. More people are choosing less-expensive alternatives such as cremation. Green burials, in which the unembalmed corpse is buried directly in the ground or in a biodegradable container, are also gaining in popularity. These new trends will drive another shift in a long history of cemeteries.

Cemeteries as a classroom

Introduce your students to local cemeteries as primary source artifacts located in your community. Be sure to review the rules for visitors when planning your visit. Encourage students to look back through time and compare historical experiences with 21st-century practices by asking the essential questions, “What do cemeteries reveal about the past?” and “Why have our customs changed or remained the same?”

Access hundreds of historical primary source activities

Try a free 30-day trial of Active Classroom

Cynthia W. Resor was a middle and high school social studies teacher before earning her Ph.D. in history. She is currently a professor of social studies education at Eastern Kentucky University. She is the author of a blog, Primary Source Bazaar, and three books on teaching social history themes using essential questions and primary sources: Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries:Modern Lessons from Historical Themes, Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies and Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies.