One of the most dramatic events in world history was the Spanish Armada in 1588, changing the direction of English, Spanish, European, and American history. It is easy to look back on this event with 20:20 hindsight and judge the foolishness of Philip II of Spain for trying to invade England. But, what if we give students the problem that Philip II faced in 1587 and ask them to make the decision about whether to invade, before they learn what happened? Without knowing the outcomes, will students make some of the same mistakes that Philip II made?

This decision-making format provides an opportunity for students to learn humility and contingency in addition to learning the historical context of a momentous event in history. The “you are there” format is also immensely engaging for many students. Use the suggested lesson plan and sources below with the excerpts of student handouts to engage student thinking and challenge their decision-making skills!

The full lesson, which is 30 pages long, can be found in Renaissance through Scientific Revolution: Decision-Making in World History and is also referred to on my website.

Procedure

Step 1: Students read the handouts and individually write down their decisions. It is important that students write down their choices before interactions with their classmates begin, so they can see how their thinking evolves on the topic.

Step 2: Students pair up to discuss their choices.

Step 3: The teacher brings the class together to vote on the decision of whether to invade England and records them for students to see. Then the teacher asks for arguments for and against war.

Step 4: The primary decision-making skill in the lesson is asking questions. Students do not get much information in the problem handout. So, the main way to get more in-depth information is through asking questions. Since students may struggle with thinking of productive questions, Handout 2 provides a list of seven questions. Students could vote on a ranking of the top three questions they would want answered, and the teacher could read the answers of the top 3 vote-getters. (See the suggested answer to one of the questions in Handout 3 below.)

Step 5: Students pair up again to reassess the decision in light of the answers to the questions.

Step 6: The class discusses the decision again and revotes.

Step 7: The teacher distributes the outcomes of the problem in Handout 4.

Step 8: The teacher leads the class in a debrief of the activity with the following questions:

- Where did Philip II go wrong in his decision making?

- Which questions were or would have been most helpful to making a good decision?

- How did students do in their decision making? What would they do differently the next time?

Sample Lesson

Use the sample lesson materials below to follow the above procedure.

Handout 1 – Problem (Excerpt)

The year is 1587, and you are king of Spain, Philip II. Spain, a Catholic country, is the most powerful country in Europe, with colonies in the Americas and in Asia. England, a Protestant country led by Queen Elizabeth, is a major stumbling block for Spain. English pirates attack Spanish ships and steal gold and silver being transported from the Americas. In addition, England is giving military backing to the Protestants who are rebelling against the Spanish in the Spanish Netherlands. Queen Elizabeth called you a heretic because you are a Catholic, which is upsetting, since you are a very religious person. This year, Queen Elizabeth had Mary, Queen of the Scots, executed. Mary was a Catholic who could have restored England to the Catholic faith. Now she is dead.

One way to solve all these problems with England is to invade the country, take it over, and replace Queen Elizabeth with a Catholic queen. It would end the government-supported piracy of Spain’s treasure ships and end English support of the Protestants in the Netherlands. A successful invasion would mean a great advance for the Catholic faith, helping to eventually stamp out all Protestantism in Europe.

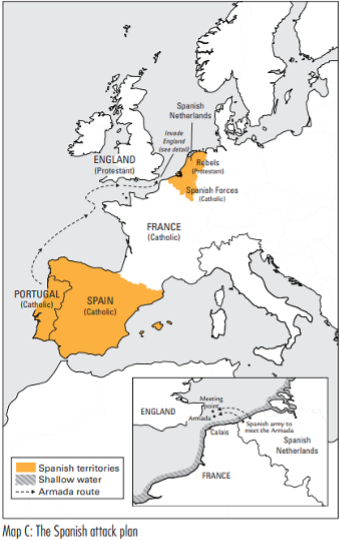

Advisers have agreed on the following plan. The Spanish fleet will sail along the south coast of England in a tight defensive formation to the coast of France. There, they will meet up with a Spanish land army of about twenty-seven thousand men that is presently in the Netherlands. The land army will be ferried out to the Spanish fleet (a distance of about 20 miles) on unarmed barges (boats), called troop transports. (See Map C) The reason the soldiers have to be ferried out to the fleet is that the water near the coast is too shallow for large warships. The land army will then be protected by the fleet as it crosses the English Channel for the invasion. Once on land in England, the Spanish army will easily defeat the untrained English army. With God on the Spanish side, the invasion plan will be successful.

Will you support or reject the invasion?

- Support the invasion. It will solve many of Spain’s problems with England.

- Cancel the invasion. It is too risky and costly.

Handout 2 – Questions (Excerpt)

- Have invasions of England been successful in the past?

- If soldiers land in England, would they have a good chance of defeating the English land armies?

- How likely is it that the Spanish fleet can defeat the English fleet?

- Is it reasonable for the Spanish fleet to meet the Spanish army in the Netherlands and then protect it across the English Channel?

- How much of a factor could the weather be in the invasion plan? How likely is it that the weather could “sink” the invasion plans?

- Will the fleet be able to hold onto enough supplies to fight the English, carry out the invasion, and follow through on the invasion?

- How expensive will it be to build and supply a fleet of this size? Can Spain afford this expense?

Handout 3 – Suggested Answer to Question #3 (Excerpt)

- How likely is it that the Spanish fleet can defeat the English fleet?

The Spanish fleet will be at a disadvantage in many ways compared to the English fleet. First, Spanish cannons are almost useless. They are not accurate and are not manned by experienced gun crews. Worst of all, the English can fire many shots, perhaps ten or more, for every shot fired by Spanish guns.

Second, the English ships are much faster than the Spanish ships. The problem of lack of speed is compounded because the Spanish fleet has to stay together. Consequently, the fleet must sail at the speed of the slowest ship. Essentially, the English ships will be able to sail circles around the Spanish fleet, firing broadsides of cannons at them, while keeping far enough away so as to avoid being hauled in close and boarded by the Spanish soldiers.

Third, the English will have the advantage of knowing the waters, tides, currents, and winds off the coast of England. They will know when to attack, where to locate their ships, and when to retreat. They will be able to draw Spanish ships into traps, based on superior knowledge of the currents and tides near the shore. Also, since the English will be near their own ports, they will be able to resupply and repair their ships, whereas the Spanish will not.

Fourth, the commander of the Spanish fleet died this year, and the new commander is less experienced. Also, he stated in a letter that he thinks the fleet attack on England is a great mistake with little chance of success. The commander of Spanish land forces in the Netherlands also thinks Spain should make peace with England. He urged in a letter to “conclude peace . . . by this means we should end the misery and calamity of these States . . . and we should escape the danger of some disaster.”

Handout 4 – Outcomes (Excerpt)

The invasion was a disaster for many reasons:

The invasion was a disaster for many reasons:

- The construction and assembling the fleet was delayed for over a year, costing Spain the equivalent, in modern U.S. currency, of fifty million dollars per month.

- When the Armada commander sent a note saying the fleet had arrived at the meeting point off the French coast, the commander of the Spanish land forces replied that the land army would not be able to transport out the meet the Amada for six days.

- In the meantime, the English sailed fire ships into the Spanish fleet on the evening of August 7. Any Spanish ship—made entirely of wood, cloth, and rope—touched by a fire ship would also catch fire. Since there was not enough time for the 120 ships to pull up their anchors, the terrified Spaniards cut the ships from their anchors so they could float away on the tides. No Spanish ships caught fire, but the fleet was scattered—the tight defensive formation was broken. When dawn came, the English ships closed in on the Spanish ships, blasting them with cannons. Five Spanish ships were sunk while many other ships were damaged, some severely.

- The wind pushed the Spanish ships north and the Spanish commander decided the keep going north, sailing around Scotland and Ireland to get back to Spain. Without enough water and food, thousands of Spanish sailors died. Storms pushed many Spanish ships, without anchors, onto the rocks on the Irish coast where they sank.

- By the time the Armada got back to Spain, at least fifty ships out of the original 129 had been lost. About twenty thousand Spanish sailors and soldiers (out of thirty thousand in the whole force) were lost.

- The Spanish did not sink a single English ship, and no Spanish soldier stepped foot on English soil. Only about thirty-six English sailors were killed in battle. The carefully planned invasion was a total failure.

- The loss of the Armada crippled Spain’s reputation as a dominant power in Europe and America. The Spanish people had to pay higher taxes to pay for the losses. They felt their king, Philip, hurt Spain with his foolish decision to try to invade England.

Selected Sources

Adams, Simon. “The Lurch into War.” History Today, 38 (May, 1988), 19–25.

Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe. The Spanish Armada. New York: Oxford, 1989.

Hutchinson, Robert. The Spanish Armada. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2013.

Mattingly, Garrett. The Armada. Chap. 25, 26. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959.

Morgan, Hiram. “Teaching the Armada: An Introduction to the Anglo-Spanish War, 1585–1604.” History Ireland, 14, no. 5 (September–October 2006), 37–43.

Parker, Geoffrey. “Why the Armada Failed.” History Today, 38 (May, 1988), 26–33.

Get a free trial of Active Classroom to try these decision-making in world history lessons with your students!

Kevin O’Reilly taught history for 39 years, all but four of those years at Hamilton-Wenham Regional High School in Massachusetts. He is the former NCSS Social Studies Teacher of the Year, along with several other awards, and is the author of 31 books on critical thinking and decision making in history. He is a climate activist and enjoys riding his bike. You can see his free critical thinking and decision-making lessons at www.criticalthinkinginhistory.com