How does a teacher narrow down over 5000 years of human history and culture for the classroom? Use essential questions!

Essential questions transform a “one darn thing after another” approach into a thought-provoking, inquiry-based classroom. A good essential question requires students to use higher-order thinking skills. And if chosen carefully, essential questions encourage students to make connections between classroom topics and issues in their own lives.

Here’s an example. Imagine the usual, chronological units in European or American history: ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, colonial America, Revolutionary War, and creating the Constitution. Too many students roll their eyes and wonder “How is this related to me?”

But what if you started the school year with this essential question:

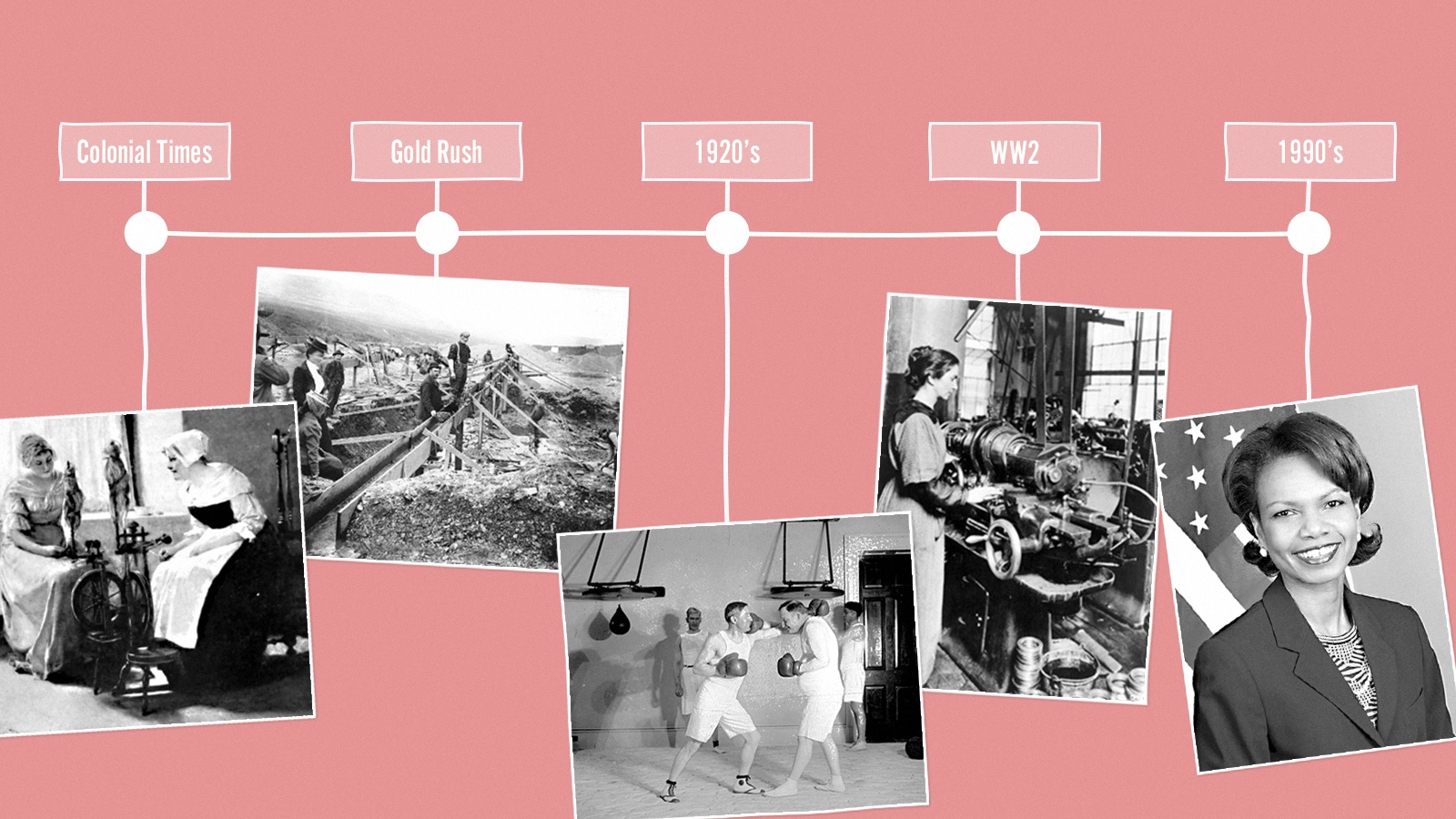

Why are men and women expected to act differently?

This question is relevant to social studies disciplines: history, culture, geography, sociology, psychology, government, and even economics. It has the potential for interdisciplinary study across the entire curriculum.

Explore digital DBQ activities with a free 30-day trial of Active Classroom

Introduce the essential question as the theme for the school year

Begin the year by introducing the question and asking students to reflect on their own daily experience individually in short written responses, comparing and contrasting answers in small groups or within a whole class discussion. Ask additional thought-provoking questions relevant to the course such as:

- Do different cultures have different expectations for male and female behavior?

- Are the differences between men and women learned or biological?

- Are men and women treated differently in schools? In the workplace? In the marketplace? By government? Why?

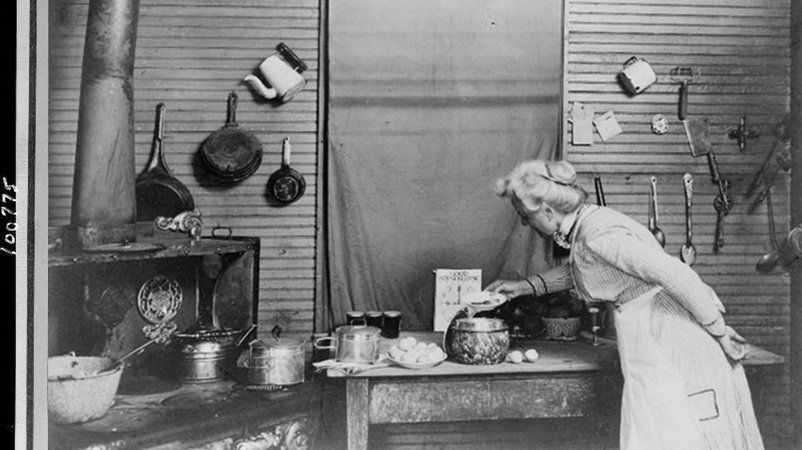

After you have set the stage, revisit the essential question in every unit and in different contexts. Provide intriguing quotes or images appropriate to the topic at the beginning of units and lessons. Here are a couple of examples:

“A man’s face is his autobiography. A woman’s face is her work of fiction.”—Oscar Wilde, 1898 (See references)

“If it were customary to send daughters to school likes sons, and if they were then taught the natural sciences, they would learn as thoroughly and understand all of the arts and sciences as well is sons. . . just as women have more delicate bodies than men, weaker and less able to perform many tasks, so do they have minds that are freer and sharper whenever they apply themselves.”—Christine de Pizan, 1404 (See references)

How did this pair of Currier and Ives prints reflect different expectations for men and women? According to 19th-century etiquette manuals, couples were to avoid sexual relations until after marriage and the woman was expected to be a moral “gatekeeper” who said no.

Essential questions achieve three goals

According to Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins, good essential questions have three key qualities that make them ideal for the social studies curriculum.

1. Timelessness

Good essential questions stress a key theme over the span of human history, providing “glue” for instructional units throughout the year. A timeless essential question recurs over and over again in students’ lives, throughout human history, and in virtually any topic in social studies.

For example, even if your curriculum is mostly focused upon political events, asking students why men and women are expected to act differently highlights dissimilar portrayals of the actions and motives of female and male rulers through time. A seemingly social-history question now becomes relevant to political events.

As portrayed in history, female rulers seem to always be influenced by men in tragic love stories while male rulers appear to make their decisions free of irrational influences. Cleopatra (69–30 BCE) and Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122–1204) were both educated and powerful rulers in their own right. Both engaged in lifelong struggles to preserve their lands from powerful neighbors. Ancient Egypt was threatened by Rome; and both France and England hoped to acquire Aquitaine. But in many modern texts both of these smart, powerful women appear in background roles, making decisions based only on love rather than political and economic realities.

Follow up by asking students to analyze how modern female and male leaders are portrayed in the media. Do differences still exist?

In this example, our essential question provides a deeper way of looking at political events in history even though our question is one of a social nature. Good essential questions are ubiquitous throughout time, cross disciplinary lines, and relate to modern issues.

2. Foundations in the discipline—historical literacy

Historical literacy—the skill set historians use to read, analyze, discuss, and write about primary source documents, images, and artifacts—is the foundation for good social studies instruction. Essential questions guide primary source choices throughout the school year. With our sample essential question we’ve been using, it’s easy to find related primary sources. Etiquette advice for men and women exists from almost every historical era. The next step is to simply choose relevant documents for each unit and ask students to compare them to the recommended behavior in previous eras.

In 1884, etiquette expert Mary Elizabeth Wilson Sherwood (1830–1903), advised readers that chaperones were required during courtship, even for engaged couples.

“Nothing is more vulgar in the eyes of our modern society than for an engaged couple to travel together or to go to the theatre unaccompanied, as was the primitive custom. This will, we know, shock many Americans, and be called a “foolish following of foreign fashions.” But it is true; and if were only for the ‘looks of the thing,’ it is more decent, more elegant, and more correct for the young couple to be accompanied by a chaperon until married. Society allows an engaged girl to drive with her fiancé in an open carriage, but it does not approve of his taking her in a closed carriage to an evening party.”

Follow up by asking students questions that explore your essential question in a similar, modern context: “What are the rules for relationships in 2018? Are females and males expected to act differently? Do some rules apply to both? Do relationship rules restrict one sex more than the other?” Essential questions create an opportunity for students to deeply interact with primary source analysis and apply their knowledge at deeper levels, reinforcing historical literacy.

3. Learning key facts, concepts, and skills

Higher-order thinking requires remembering social studies facts, important people, places, and events, as well as the historical literacy skills discussed above. Essential questions are a framework for organizing and remembering all those important details.

For example, John Adams, second president of the United States, might not be memorable for a typical middle or high school student. After all, there are 44 other presidents to remember and two are named Adams! But what if he and his son, John Quincy Adams, are introduced through the eyes of their wife and mother, Abigail? Men and women were expected to act differently in 18th–century America, but Abigail Adams’s letters demonstrate that many questioned social norms. Asking essential questions such as Why are men and women expected to act differently? becomes a device for remembering the American presidents. Essential questions connect a wider story to facts and dates to make them more memorable.

Conclusion: Challenge your students with essential questions

Good essential questions improve the social studies curriculum in multiple ways. They highlight timeless themes that are relevant to the past and the daily lives of students. Teaching critical analysis and historical literacy becomes more focused with primary source texts and images targeted to answering the essential question. Meanwhile essential questions become the glue that cements people, places, and events in students’ memories.

Explore digital DBQ activities with a free 30-day trial of Active Classroom

Cynthia W. Resor was a middle and high school social studies teacher before earning her Ph.D. in history. She is currently a professor of social studies education at Eastern Kentucky University. She is the author of a blog, Primary Source Bazaar, and two books on teaching social history themes using essential questions and primary sources: Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies and Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies.

References

Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins, “Chapter 1. What Makes a Question Essential?”

Quote attributed to Oscar Wilde by Robbie Ross–in The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde, eds. Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis (New York: Henry Holt, 2000), 1055.

Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, trans. Earl Jeffery Richards (New York: Persea Books, 1982), I.27.1; 63.

For more about essential questions related to the daily lives of students by this author, see her books:

Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies |