Women’s roles are often overlooked when teaching about the economy of the ancient world. For example, Mediterranean economy lessons focus on shipping and sea trade in food, metals, pottery, early written records of trade, and luxury goods. However, these individuals, sailors, metal workers, farmers, scribes, were men. Wealthy women occasionally appear as consumers of trade goods, such as expensive bronze mirrors, glass bottles of perfumes, and ivory containers of cosmetics, but where are other women represented? The work of average women is often forgotten in history textbooks.

The everyday and never ceasing work of women in textile production and trade is rarely highlighted. Why?

Historical Context of Textiles and Trade

The earliest woven textiles came into use in the following order: linen from the flax plant (developed c. 8000 BC in the Near East); silk from silkworms (c. 5000-3000 BC in China); cotton from the cotton plant (4000 – 3000 BC in India), and wool from sheep (c. 3000 BC in the Near East). All four of these earliest fibers required multiple, time-consuming processes to make fabric. Fibers were spun into thread or yarns by hand using a drop spindle and distaff.

Much of our knowledge of ancient trade goods comes from archeological evidence and the discovery of ancient, wrecked ships. Textiles don’t survive in water and deteriorate over time in cool, wet climates. Knowledge of ancient shipping trade around the Mediterranean Sea often comes from re-discovered shipwrecks. The late fourteenth century BC ship, the Uluburun, was discovered off the coast of Turkey in 1982. This ship, mostly likely Phoenician and destined for Greece, contained both raw materials and finished products – metal, glass ingots, pottery jars to store goods, jewelry, weapons, tools, and food. If textiles were present, sea water destroyed them.

The ancient textiles that did survive were primarily found in hot, desert climates such as Egypt. Furthermore, everyday textiles and the clothing of average people were used until they were completely worn out. No one could afford to throw away usable fabric because textile production was time consuming and expensive. This absence of evidence often leads us to forget who was behind the creation of these textiles. Average ancient people certainly didn’t donate a carload of out-of-style clothing at the local thrift store.

Additionally, historians found that ancient Minoan Crete was a center of textile production for export. By 2300 BC, sheep bred for high quality wool were herded on the island and large textile production shops produced both wool and linen fabrics for export. Minoan women created bright, beautiful woven fabric in blue, red, yellow, and white prized across the Mediterranean. Dying fabrics was yet another laborious process that added value to textiles. Some dyes were created from plants such as madder for blue or saffron lilies for yellow. The cochineal insect produced red. But all dyes require chemicals to fix the dye in the fabric, and some dyes such as indigo or the purple from the murex sea snail required extensive processing.

The machine we know as the spinning wheel did not come into wide use until the Middle Ages. The yarns or threads were hand-woven using looms and finally, finished cloth was sewn into clothing or household goods such as sheets, towels, curtains, sails for ships, and much more. Almost all of this work was done by women, both free and enslaved, for use in the household or for sale.

Historical Context of the Role of Women

The daily roles of women were often dismissed or ignored by archeologists and historians until recent decades. Previous archeologists searched for gold, silver, and other ancient treasures and tossed aside the surviving relics of everyday life or the textile industry, such as loom weights. These loom weights are small tools made of baked clay, usually pyramid or cone-shaped, required when weaving on a vertical, warp-weighted loom. They were integral to understanding the daily role of women as homemakers and textile workers.

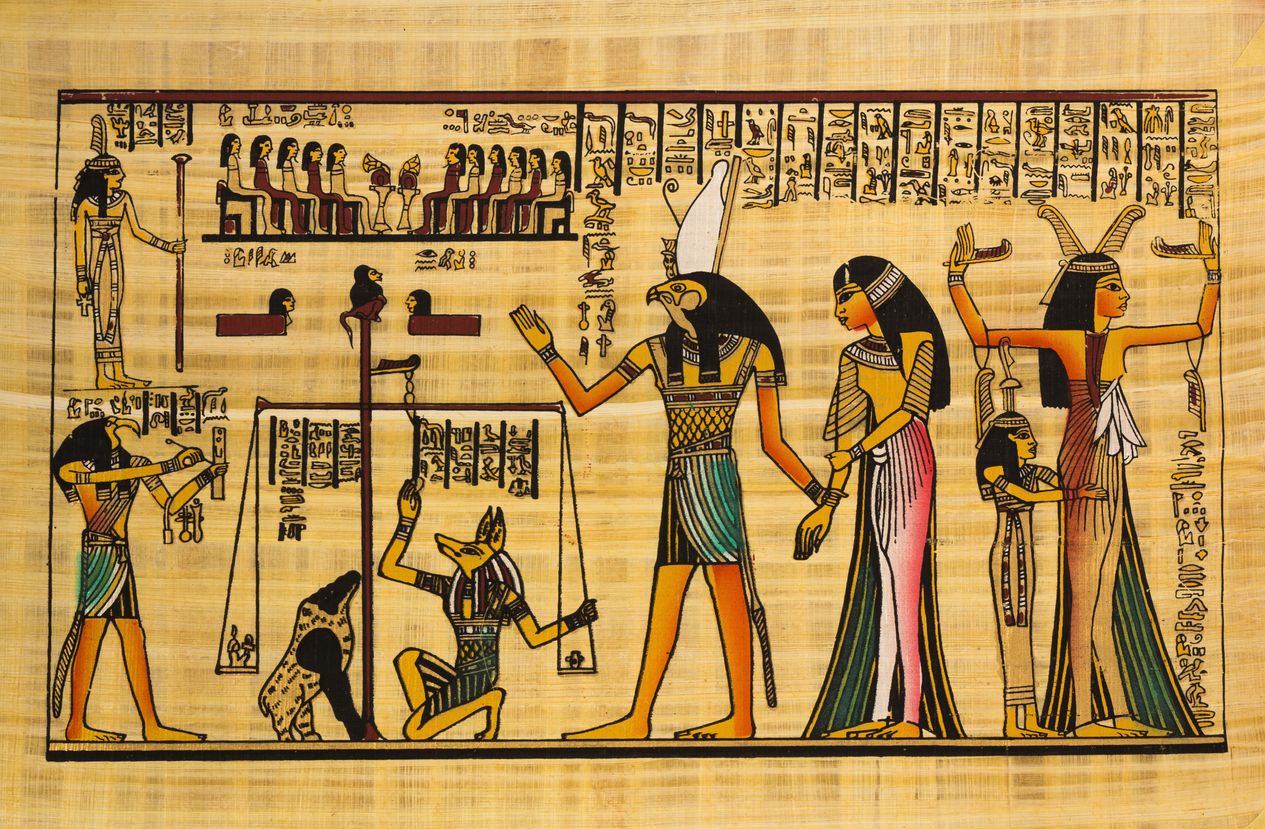

In ancient Egypt, large workshops of women, often enslaved, spun and wove flax fibers into linen, the fabric used by every Egyptian from birth to the grave. Egyptian funerary texts note that linen cloth was a prized funeral gift and royal tombs contained high quality linen fabrics that would have taken months to produce. Mummies were wrapped in linen strips, ships sailed using linen sails, fisherman made nets from linen fibers.

In most ancient cultures, women were responsible for having and raising children, food preparation (and often food production and preservation as well), and textile production. Experts note that daily food preparation and textile production are both easily compatible with caring for small children and women could attend to all three of these tasks at one time. Although women participated in multiple roles in society, as homemakers and textile workers, their contributions are rarely highlighted outside of the childcare or home setting. Teachers can continue to highlight both the societal expectations of women during the time period and their economic contributions as workers.

Classroom Activity

In your classroom, compare and contrast the textile economy of the ancient and modern world. Very few women today labor for hours spinning, weaving, and sewing. On the other hand, a significant part of the lives of ancient women was spent creating textiles to provide for daily needs as well as contributing to the wider economy and trade. Make comparisons between our present world of overly abundant “fast fashion” produced inexpensively in factories and the ancient world when all textiles were labor intensive products and highly valued. Only the wealthiest ancients had a closet and home full of clothing and fabric furnishings. These activities will help students to build essential compare and contrast skills as well as critical thinking about how the societal and economic expectations of women have changed over time.

Get a free trial of Active Classroom to explore more economics instructional resources.

References

Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years by Elizabeth Weyland Barber, 1996

Textiles in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cynthia W. Resor is a recently retired social studies education professor and former middle and high school social studies teacher. Her dream job? Time-travel tour guide. But until she discovers the secret of time travel, she writes about the past in her blog, Primary Source Bazaar. Her three books on teaching social history themes feature essential questions and primary sources: Discovering Quacks, Utopias, and Cemeteries: Modern Lessons from Historical Themes; Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies and Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies.