More and more often, history teachers are being asked to structure their curricula thematically as opposed to chronologically, in hopes of increasing student engagement and facilitating comparison among multiple perspectives.

At the same time, Common Core and other state standards require that students engage directly with primary source documents as opposed to textbooks alone. Yet teachers have few resources and little guidance when trying to implement or combine these principles.

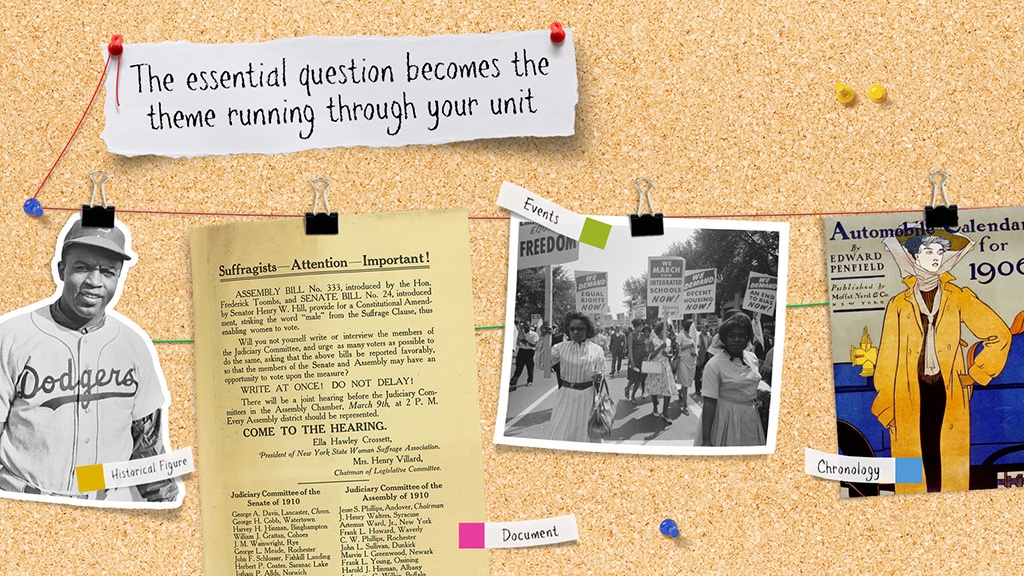

Start with an essential question

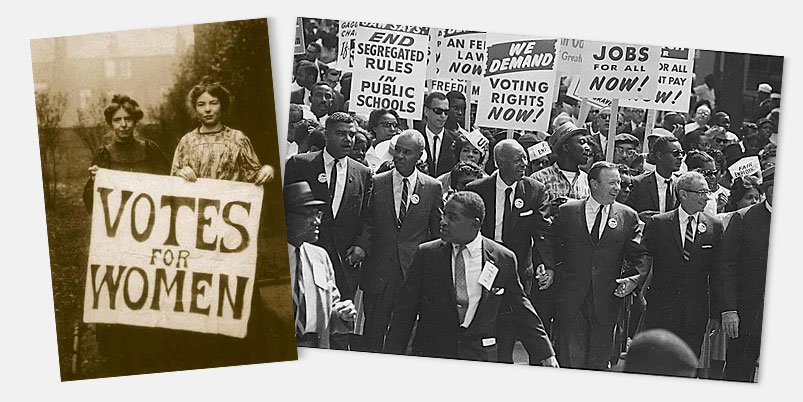

Luckily, designing thematic, document-based history units is easier than it may seem. The first step is to identify an essential question (McTighe & Wiggins, 2013) that has recurred over time. Essential questions promote critical thinking, but yield no easy answers. For instance, in U.S. history the question “What does equality mean?” came up in the country’s early years during the run-up to the Civil War, during the suffragists’ fight for the vote, during the Civil Rights movement, and in recent debates about same-sex marriage. Likewise, in world history, the question “What is worth fighting for?” has been answered in different ways at various times by people around the world.

Link your question to individuals

Once you have an essential question, think of 8–12 historical figures who have offered answers to this question. In order to ensure a diversity of perspectives, go for variety in terms of gender, race or ethnicity, class background, political ideology, and historical era. Be sure to choose one figure from the recent past so the question’s relevance to the present will be clear.

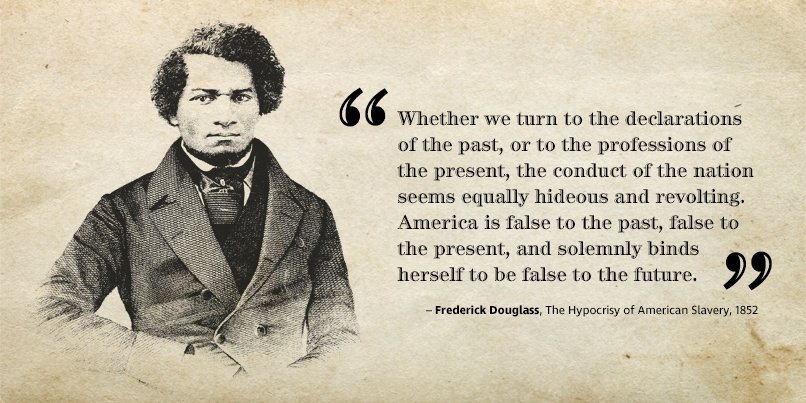

Link your historical figures to documents

Find a document that illustrates each historical figure’s perspective; it might be one they wrote or one that refers to them. The next challenge is to abridge the document to focus on the excerpts most relevant to the essential question. For the secondary level, I recommend an excerpt of 400–500 words so that it is substantive enough to withstand analysis but short enough to read during a class period. I find that one major reason that teachers hesitate to use primary source documents is that they can be unwieldy and difficult for students to understand. Yet with the essential question in mind, it is often possible to trim a document down to focus on the concepts you want to highlight. You may also wish to identify the vocabulary in each document that is likely to be unfamiliar to students so that you can pre-teach it or develop strategies that would allow them to decode meanings as they read.

For each document excerpt, consider the background knowledge students would need to place it in context, then prepare an introductory reading and/or a mini-lecture that will help them make sense of it. For instance, if you want students to read Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, they will need some background on the Civil War.

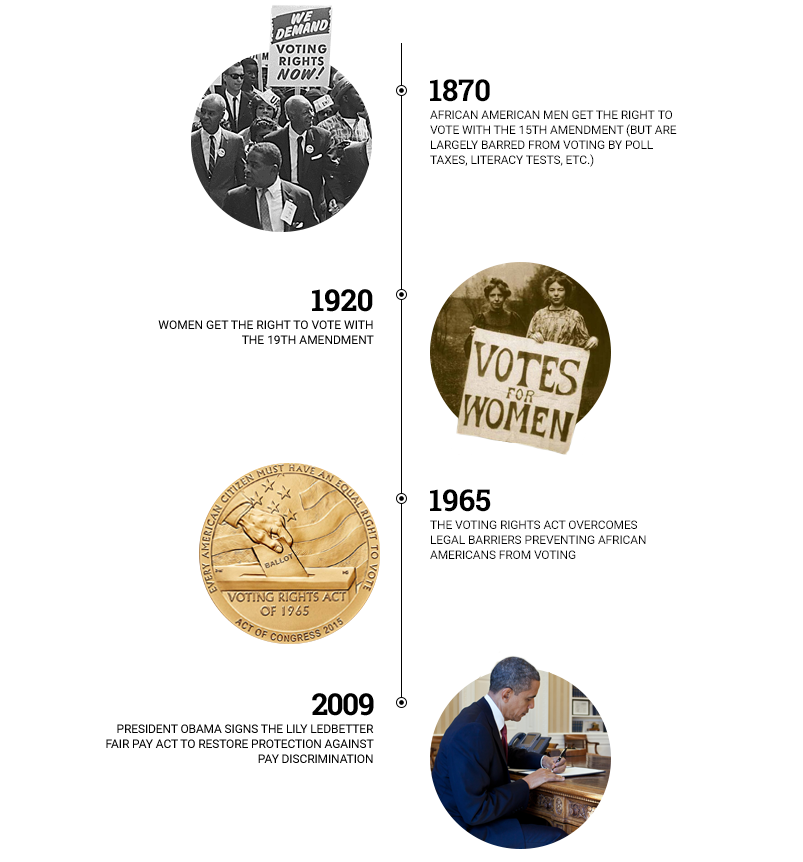

Link documents to historical events to establish chronology

At this point, teachers often hesitate. If students aren’t moving chronologically through history how will they build up knowledge about history and be able to sequence events? I recommend associating each document with a historical event, and having students keep timelines on which they place each new event, as well as keeping a class timeline that is always visible. If you move through seven to ten thematic units over the course of one year, students will have plenty of opportunities to revisit events and historical eras. Instead of the “learn it, then forget it” approach to teaching history, organizing the curriculum thematically encourages students to constantly reassess their understanding of the past.

Plan your lessons for each document

Once you have chosen your historical figures, excerpted your documents, and identified the events associated with each one, you are ready to plan the lesson for each document. Think of a question or activity that could capture students’ attention, activate their prior knowledge, and prepare them to engage with the document. For instance, before reading an excerpt of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War students might consider the steps they would take if they were army generals planning an attack. After students are “hooked” into the topic you can provide them with the background reading and/or a mini-lecture that will frame the document. Analyzing the document itself can be done in many ways, including through shared reading, independent reading, or having students work in pairs or small groups.

Assess comprehension, then assign activities that develop higher-order thinking skills

Once they’ve finished, you’ll need a couple of questions to assess their comprehension before moving on to an activity that asks them to use higher-order thinking skills. Activities could include class debates about one of the document’s propositions or opportunities for students to link the new document with those they’ve read earlier in the unit—for example, by imagining a dialogue between the document’s author and another historical figure in the unit. Finally, a reflection activity that refers back to the lesson introduction or encourages students to situate what they’ve learned in the overall context of the unit can help them synthesize what they’ve learned.

Completing your unit and planning to begin

Now you have 8–12 lessons designed around historical documents, and your unit is almost complete. Consider starting your unit with a document from the recent past in order to facilitate present-day connections. Then double back to the earliest event and proceed chronologically through the rest of the documents in your unit. I like to begin each unit by having students (or pairs of students) chose a historical figure to represent in a unit-culminating “summit” where they discuss the essential question, citing evidence from the documents they’ve read. At that point, you can also ask for students’ personal views, informed by the readings they’ve done. What IS worth fighting for? What DOES equality mean? Your students’ answers are sure to impress you now that you’ve given them the material with which to form an educated opinion.

Subscribe to get engaging social studies content your students will love: primary-source based activities, digital lessons and more!

Get engaging, interactive digital activities for your social studies classroom

Try a free 30-day trial of Active Classroom

Resources

McTighe, J., & Wiggins, G. (2013). Essential Questions: Opening Doors to Student Understanding. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Rosalie Metro is an assistant teaching professor in the Department of Learning, Teaching, and Curriculum at the University of Missouri-Columbia, and the author of Teaching US History Thematically: Document-Based Lessons for the Secondary Classroom. She formerly taught middle and high school social studies, and now works with pre-service teachers.

Hi Rosalie, I bought your book and have found it to be a wonderful approach to teaching US history. I teach U.S. History and World History on alternating years in a small progressive high school. I will be teaching World History next year — modern world history — and I’m curious as to whether you have seen a curriculum designed thematically for that content the way you designed one for US history. My compliments on your brilliant work.

Considering using a thematic approach next year in US/NC history. Great resources!