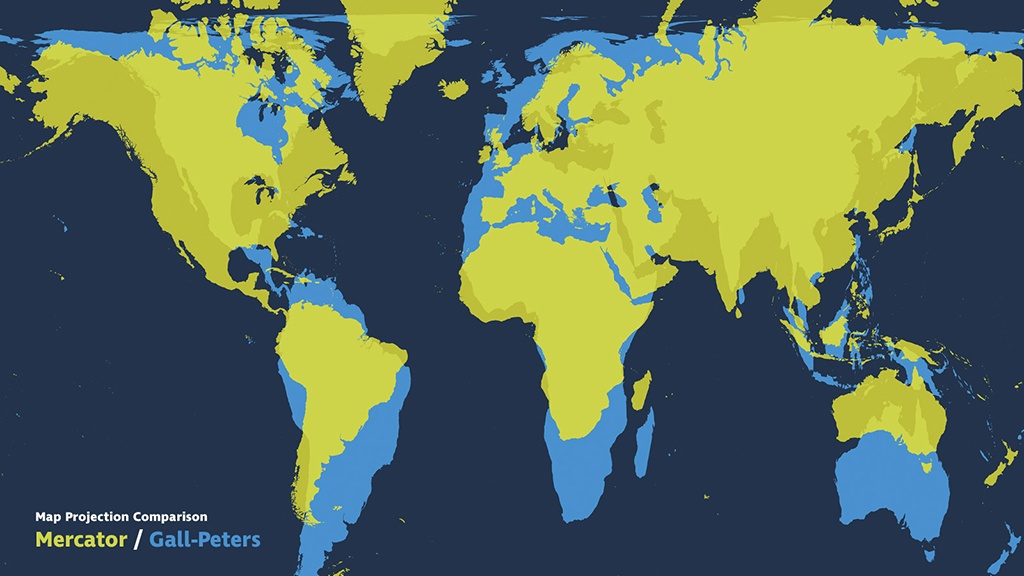

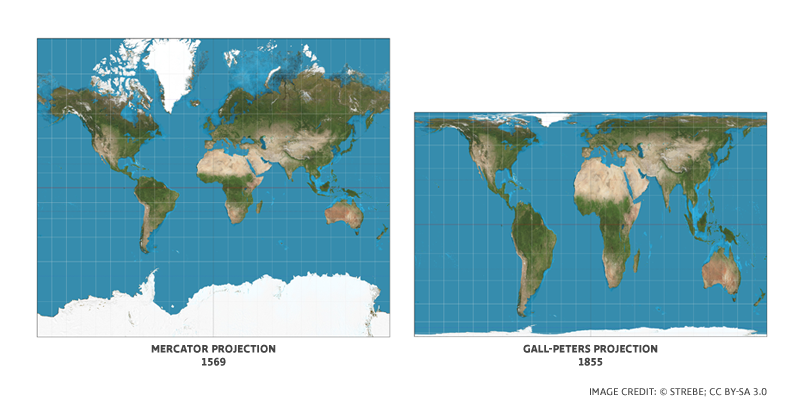

Here you see two examples of map projections of our incredible world. It won’t take the average student long to notice that these two maps are significantly different from one another.

While sailors have employed the Mercator projection to successfully navigate the open seas, and classrooms have employed it to study geography, the map does not depict an accurate representation of the sizes of our continents in relation to each other. Practicing questioning can challenge students to analyze the differences in these perspectives of planet earth in ways that are meaningful and memorable to them.

Begin by posing questions

Pose questions to students to help them understand that maps are an abstraction of reality. Here are some examples of questions to consider when helping students digest new material.

-

Is it possible to create a perfect abstraction of reality?

-

Check out the evolution of these projections over time. What do you notice? (Africa has been depicted as comparable in size to Greenland in traditional designs. In actuality, we could squeeze the United States and China into Africa, and still have space left over for Australia and the Hundred Acre Wood.)

-

Have you ever considered before, that the map hanging in the front of your classroom that you spend a fair amount of time studying, was less than 100% accurate?

-

If this map is not necessarily reality, then what else in the world could in fact be different than you have perceived?

By building the foundation for thought and question patterns such as this, you can help students to begin to educate themselves on a more intuitive level than they ever imagined.

Use questions to introduce disciplinary tools and actions

Using questions is also a great method of introducing the tools geographers use such as longitude and latitude. Instead of giving them a pat definition to preview the concepts, encourage them to dig right in by finding their own answers. Ask:

-

Does reality equal perfection? How do we measure perfection? How do we determine how close to perfection our representation actually is?

-

What exactly are the functions of a map and what do we need it for?

-

Can we pinpoint our destination on a map? How?

Can we calculate how far point A is from point B? Is this the purpose of a map? How many purposes does a map have?

Use questions to teach evaluating maps as sources

Maps are sometimes relied on as unbiased sources. Not all sources are created equal. Accuracy is being questioned widely in our time, and it is no different for mapping. Just as when they analyze other sources such as news sites or books, students need to use research skills to make conclusions and determine what maps can best reinforce their arguments. While evaluating these projections, students should pose questions that challenge their credibility.

-

Can a map be biased? If so, how can a map be biased?

-

How can a map reinforce an argument?

In the projections above, could there be any ulterior motives for why some countries may be portrayed as larger than others?

Use questions to help students take informed action

Our world is spherical, maps are flat—you do the math. Now it’s time for students to form their arguments and plans of action. Using these questions, challenge your students to debate the steps they would take to form an accurate visual of our world.

-

Would they develop a projection similar to the Mercator? To the Gall-Peters? Ask students to choose which projection they like best, (or neither) and provide evidence supporting their decision.

-

Or would they take a completely different approach? Have students research other projections that have been created over the years. Are there any they think do a better job at showcasing our world?

-

Have students focus on a globe. Ask them to visualize taking that globe and breaking it down to a flat map. What would be the best strategy to achieve this?

Asking good questions is a part of our everyday life, and we need to encourage students to understand that inquiry is a crucial component of growing. Teach them that questions do not indicate the fact that we do not know something but rather that we have both the capability and the desire to learn and grow. Give your students permission to be curious, and therefore, the gift of learning.