The history of ordinary people and everyday life appeals to students. However, teachers struggle to squeeze it into a social studies curriculum dominated by stories of wealthy elites and political chronology. Narrowly defined disciplines and state-mandated teaching standards often leave little room for social history. However, essential questions focusing on daily-life themes relevant to student’s lives are the perfect solution for introducing more social history in social studies curriculum.

Why teach social history?

Social history, sometimes referred to as “history from the bottom up,” is the study of the lives of ordinary people: those who were not the elite, wealthy, and politically powerful. Social history not only provides a historical context for everyday experience, but also offers an analytical perspective for students to examine their own lives.

Social history also focuses upon “big changes” or turning points in history impacting daily life. The causes and effects of social change do not always easily fit into typical instructional units driven by timelines, dates, kings, presidents, and wars. For example, social changes driven by the Industrial Revolution developed over decades–the history of which spans many typical instructional units. The revolutionary impact of industrialization on daily life is lost when social history lessons are inserted sporadically in the curriculum.

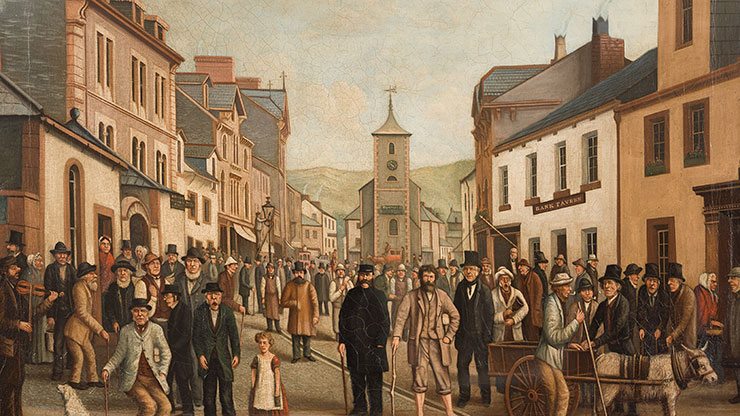

Photo: Library of Congress

Make social change relatable and meaningful to students

To begin with, focus on just one or two elements of daily life and develop a good essential question to revisit in every unit. For example, food is a hot topic in modern America and is an excellent daily-life theme for courses in all areas of social studies curricula–history, culture, geography, sociology, psychology, economics, politics, and current events. Every student eats, has favorite foods, and is bombarded with media advice on the newest healthful and unhealthful food trends. Students can compare their own food knowledge and experiences with those of ordinary people in different cultures, past or present.

To narrow down the focus of a social-history theme, develop one or two essential questions for students to consider, assess, and reassess in each unit. Here are two ideas for narrowing the focus of a huge theme like food:

Essential Question 1: How do changes in technology impact food choices?

In the “Exploration and Colonization” unit, we typically teach that inventions in sailing technology resulted in new foods on the table in both Europe and the Americas. Potatoes, tomatoes, squash, maize (corn), turkey, and chocolate were introduced in Europe and Africa. Apples, bananas, wheat, pork, and citrus fruits were new to the Americas. However, don’t just examine lists of the foods exchanged. Use the essential question to dig deeper. Encourage students to think critically about food exchanges today as well by examining the impact of modern globalization trends and transportation technology on 21st century food choices.

Typically, lesson plans on the new technology of the 19th century Industrial Revolution focus upon trains, telegraphs, and assembly-line machinery. Instead of examining each of these in a general way, revisit the essential question by asking how new technologies changed the food supply. For example, in the early 19th century, the widespread introduction of the kitchen stove made home cooks abandon hearth cooking, the method used for thousands of years. Later in the century, home cooks were adapting old recipes and inventing new ones. Instead of using ingredients from their own farms and gardens, home cooks began to incorporate manufactured “convenience” foods in cans and packages in their recipes. Industrialization completely changed thousands of years of human food production, preservation, and preparation!

Essential Question 2: How does government policy and regulation affect food choices?

In an ancient Rome unit, don’t just focus your primary source descriptions on banquets of the rich and powerful, where expensive and exotic foods like flamingo tongues were consumed. Investigate the Cura Annonae, the government-subsidized and regulated grain supply consumed by the ordinary citizens of Rome. What might have resulted if the government had not established policies to provide affordable food in the city of Rome? Explore government’s role in feeding its citizens, in ancient times and today.

Revisit the essential question again when studying the Middle Ages. Medieval city and town laws regulated the quality and prices of essential foods like bread and ale, and the work of millers, bakers, and brewers. Today, the American Food and Drug Administration still regulates additives and food safety. How would our food choices be different if the quality of our food supply was not regulated by the government?

Revisit the essential question again when studying the Middle Ages. Medieval city and town laws regulated the quality and prices of essential foods like bread and ale, and the work of millers, bakers, and brewers. Today, the American Food and Drug Administration still regulates additives and food safety. How would our food choices be different if the quality of our food supply was not regulated by the government?

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 are cited in most Progressive era units. Use the essential question to promote higher-order thinking skills and explore how businesses, consumers, and government wrangled over and compromised to pass “pure food” legislation. Ask students to compare compromises between the stakeholders of this Progressive era legislation to modern school lunch legislation such as the controversial Obama era Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 and recent modifications by the Trump administration.

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 are cited in most Progressive era units. Use the essential question to promote higher-order thinking skills and explore how businesses, consumers, and government wrangled over and compromised to pass “pure food” legislation. Ask students to compare compromises between the stakeholders of this Progressive era legislation to modern school lunch legislation such as the controversial Obama era Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 and recent modifications by the Trump administration.

In a World War II unit, go beyond teaching about the battles and generals to focus upon the balance between feeding troops and feeding citizens at home during war. Explore the British colonial war policies that contributed to a 1943 famine in Bengal in which millions of people died from starvation or malnutrition. When discussing the American home front, use the essential question to explore food rationing and its impact on daily life. Ask students to consider the expansion of government regulations during wartime and imagine the impact of food rationing on their own lives.

Social history, or the history of daily life, has an important role in the social studies curriculum. Examining daily-life themes over the course of a school year captures the interest of students. Developing an essential question around daily life and continuing to revisit and ask it in different eras and contexts takes social history to a new level. Your students will be motivated to think critically about the past and present.

Explore hundreds of digital activities with a free 30-day trial of Active Classroom

Cynthia W. Resor was a middle and high school social studies teacher before earning her Ph.D. in history. She is currently a professor of social studies education at Eastern Kentucky University. She is the author of a blog, Primary Source Bazaar, and two books on teaching social history themes using essential questions and primary sources: Investigating Family, Food, and Housing Themes in Social Studies and Exploring Vacation and Etiquette Themes in Social Studies.