Many students have trouble understanding the geographic context of United States history even though they can often relate the themes to their lives. When teachers move to world geography, the problem of relating to the content is compounded many times over. Students rarely have the background knowledge or geographic literacy to understand where things happened in the past. Thus, making the connection between distant places and history to modern society and their own lives can be very difficult.

The C3 Framework offers teachers a path to give students relevant context to understand world history. Beginning with the four dimensions of the Inquiry Arc, we can help students develop their own questions and then incorporate the disciplinary lens of geography as they create their own maps. We can then tie those same questions and maps to the development of geographic knowledge while students “communicate results” and make connections between past and present.

The lesson format can be broken down into a four-step process: read, question, map, and connect. Let’s tackle each of these learning modalities in turn. My example is from the Nystrom Atlas of World History West African Kingdoms unit because the historical context allows us to connect the exotic and unfamiliar to students’ 21st-century lives.

1. Read to create context

To start, provide students with a short reading to introduce the period. Try to provide a broad overview and keep it short. Here is a sample of what I use for the African Kingdoms unit:

With the fall of Ancient Egypt and Kush came the rise of many other African cultures and civilizations. The first were the Bantu and Axum, cultures indigenous to Africa. The Bantu people began emigrating from western Africa in 500 BCE. As they spread south and east, they brought their innovative farming practices and metalworking skills. The Axum Empire defeated the Kush, eventually controlling the Red Sea. Through the ivory and incense trade, Axum came to control much of East Africa and the Mediterranean, spreading Christianity throughout these regions. When Axum fell, these areas were conquered by the Islamic Empires, which came to control much of North Africa. Increased trade, and later, the Crusades, brought increased contact between Islamic and non-Islamic people and expanded knowledge and learning.

In western Africa, Ghana (and later Mali and Songhai) grew wealthy on the gold trade and came to control the southern trade routes. As in the north, trade centers like Jenne and Timbuktu became important centers for learning. At the same time, Swahili culture, a mix of Islamic, African, and Asian cultures, was developing in East Africa. Cities in this region, like Great Zimbabwe, grew more populous and wealthy because of the salt, ivory, and gold trade with western Africa and Asia. (excerpt from Mapping World History by Nystrom Education)

2. Question to support inquiry

Getting students to create their own questions is an effective strategy to figure out what they find important, confusing, or compelling. Leveraging those questions to help students “own” their learning is a vital tool in the inquiry process. I ask students to generate two types of questions: essential questions and supporting questions. Essential questions (EQ) involve timeless issues that don’t have easy answers (and may not have answers at all). EQs from the reading above might be:

- Why do people trade?

- What is the relationship between trade and religion?

- How does the spread of ideas influence trade?

- Does trade lead to greater or fewer choices for consumers?

- What inhibits trade?

- Why are some items perceived as valuable?

Supporting questions (SQ) are specifically context-bound and help to clarify a particular situation. These questions have answers that are true for that particular context and may even be true for other periods and places in history by way of analogy. Some supporting questions from the reading could be:

- How did African Kingdoms become wealthy?

- What items were traded in West Africa and how were they transported?

- What were the effects of greater wealth in the African kingdoms?

The next step is to have students create a graphic organizer with two columns: one for Essential Questions and the other for Supporting Questions. Students can work individually or in groups, but they should aim to generate as many questions as they can. Remind them that there are no stupid questions and challenge them to see who can come up with the most questions. Review the questions as a class and write some of the better ones on the board, continuing to separate EQs and SQs into columns. Consider the questions a form of pre-assessment that gives insight into what students already know and what they want to learn. We will return to their questions later in the lesson.

3. Map for hands-on learning

Having students map historical events, processes, and social dynamics is an excellent way to develop geographic literacy while also providing a highly visual activity which engages the students with “hands-on” learning.

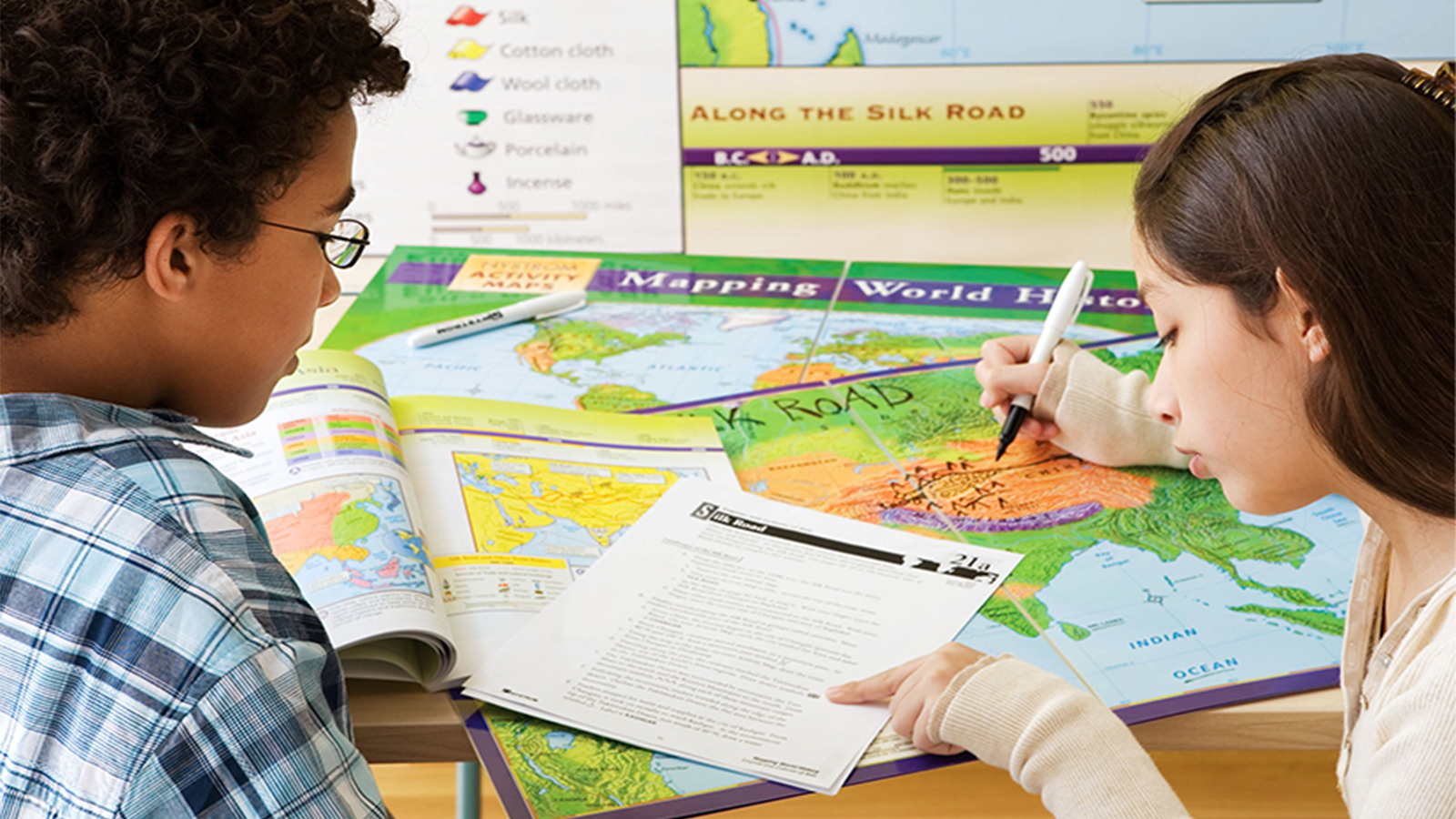

You can choose any number of maps for students to work with, many of which can be found on the Internet or within one of your world history programs. Use the Nystrom Atlas of World History for students to consult as a reference, and allow them to work online or on paper. Using symbols, lines, arrows, and words, students should map connections between people and places. With the lesson on West African Kingdoms, for example, students have to create a map that shows the location of each kingdom, what it traded and with whom, the nature of trade routes, and the consequences for religion, learning, and the exchange of cultures in general. A completed map looks something like this:

Through this activity, students interact with a map, find locations and label them, make connections between different regions, and establish the context of trade for this period in history. These skills support critical thinking, and are essential to learn at any grade level.

4. Connect student knowledge

Once students have completed their mapping activity, return to the essential and supporting questions that you began with. Review as a class to see how many of the questions they can answer. Did the exercise generate any new questions for them? If so, record those as well.

Next, use the essential questions to see if students can make connections to today. For example, “Why do nations trade?” or “Who benefits from trade?” You can then pull in examples of trade issues from the media or recent news articles. Also, if you have a copy of the Nystrom Atlas of World History, look for the culminating sections titled “Historical Issues Today.” The culminating reading for the unit on African Kingdoms asks students to reflect on the essential question “Does Trade Strengthen Nations?” Try it with your class and download here.

By connecting past with present and interacting in a kinesthetic manner as they engage with a visual resource, this activity appeals to varied student learning styles and help students to generate their own questions about the content. We consequently stand a better chance of creating meaningful learning experiences for a wide variety of students. Moreover, these multiple modalities of learning are more likely to create and reinforce a variety of neural networks in student minds leading to better retention, relevance, and recall for young learners.

Try the technique with your students. Download this sample lesson excerpted from Mapping World History by Nystrom Education:

For more geography resources, try a free trial of our digital geography platform, Nystrom World

Dr. Aaron Willis is the Chief Learning Officer (CLO) for Social Studies School Service, where he has worked in the field of interactive and digital education for more than two decades. His primary areas of interest include brain-based imaging, hands-on learning, and evidence-based reading and writing strategies. Dr. Willis oversees the development of Active Classroom and Nystrom World with an eye toward implementing the latest pedagogic strategies in a manner that is intuitive and easy to use for both teachers and students. Based in Los Angeles, California, he travels frequently to work with teachers, focusing on practical solutions to their professional challenges.